Photo of Brick Lane Bangla Town (2010)

The idea of Bangla Town in Brick Lane and the design quality of the arch and streetlamps established to physically signify this were both ridiculous.

For many Bangladeshi Londoners, the establishment of Bangla Town in the Brick Lane area represents an important achievement. They feel proud of the result of their long campaigns in generating support for and persuading Tower Hamlets Council in 2002 to rename the local ward from Spitalfields to Spitalfields and Bangla Town. The change of name and the establishment of a special arch and several street lamps represent the official recognition that parts of Brick Lane have a special historical, present and future significance for the Bengalis and that the area should be developed economically and creatively within the frameworks that included a strong Bangladeshi identity. Many felt a great sense of achievement in this regard.

Although I have always thought the idea of Bangla Town to be ridiculous, I have absolute respect for the people who first conceived the idea and those who worked hard, over many years, to transform the idea into a partial reality by helping to place Bangla Town on the map.

So, why do I still think the idea of Bangla Town to be ridiculous? I first became aware of the idea of establishing a Bangla Town in Brick Lane in 1989 when I worked as an economic researcher for the Community Development Group (CDG) on a three months contract. The CDG was engaged in producing a ‘community plan’ for parts of Brick Lane and some areas around the street, which focused on developing ideas for jointly regenerating two high-value lands – the Truman Brewery site and the Bishopsgate Goods Yard – for the benefit of the local community. At that time, as a result of the Thatcher government’s monetary policies since the early 1980s and the accelerating process of globalisation, many British inner-city areas experienced a serious decline in manufacturing jobs; an increase in unemployment, boarded-up shops and dereliction; a general downward sense of community confidence/vibrancy.

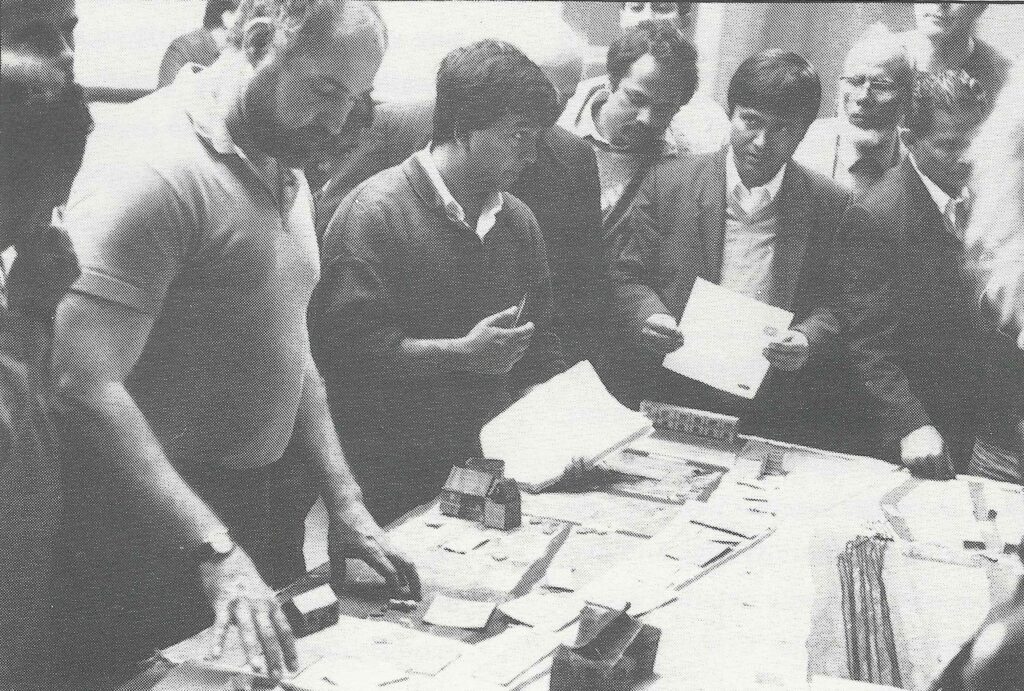

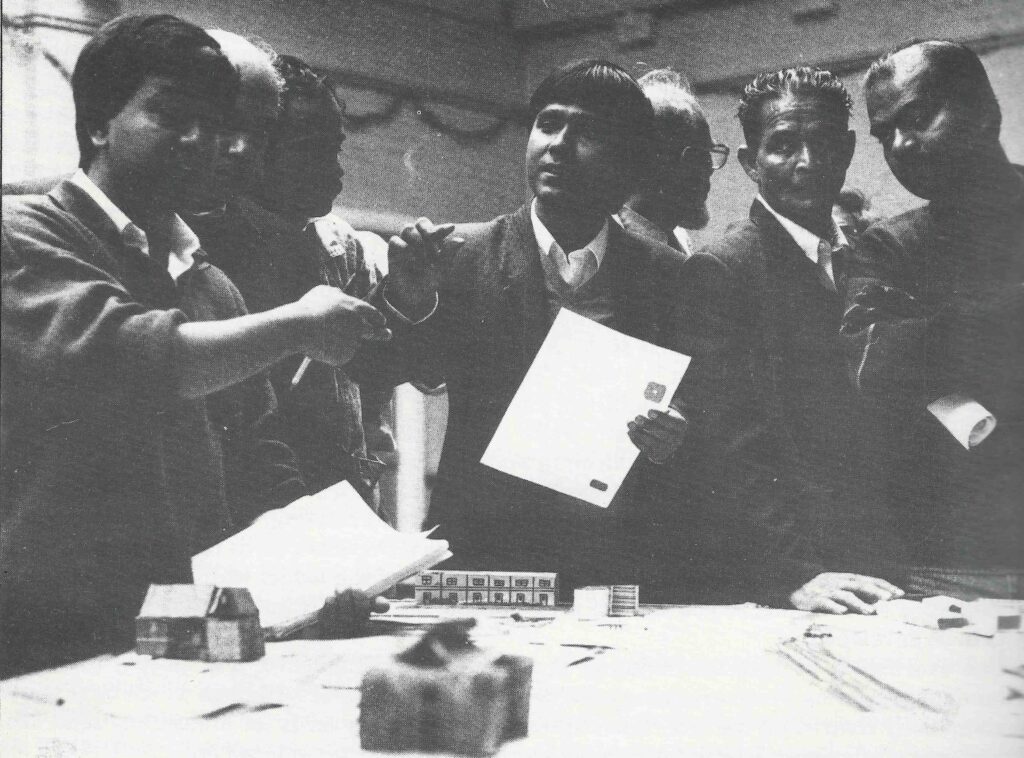

Planning for Real consultation at St Hilda’s Centre (1989)

Immediately after being re-elected in the 1987 General Election, among the promises that Mrs Thatcher made in her victory speech included one that was long-overdue: that she would now turn her attention towards inner-city regeneration. As such, in 1988, a series of task forces were announced for the country to focus on small declining inner-city areas across the nation with special efforts to kick start their regeneration. Spitalfields Task Force was created for the declining Brick Lane area (I do not remember the exact budget or the remit of the body), headed by a civil servant, to help turn things around. One of the strategies and aims of the Task Force was to help build local capacity and create an effective, good quality pool of leaders within the Bangladeshi community.

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, globalisation and the UK government’s monetary policies resulted in a huge increase in the rate of local Bangladeshi unemployment. Among the aims of the Task Force, the placing of the Bangladeshi community on a regeneration and diversification path was among the top.

The Task Force engaged with many community leaders and activists and brought them together to help form the Community Development Group (CDG). It supported and mentored individuals and groups and provided training and funding. It also engaged Business in the Community (BiC) in the project, which brought Prince Charles to provide a lending hand and spread some good words about the initiative.

With a budget of around £80,000, jointly match-funded by the Spitalfields Task Force and Business in the Community, the Community Development Group, co-chaired by Syed Ashraful Islam (who later became a minister in Bangladesh and died recently) and Shofiqur Rahman Choudhury (president of Bangladesh Welfare Association), employed several experts – including two co-directors, a community planner, a financial gain consultant, a transport professional – to work on producing a community plan. I was employed on a short-term contract to undertake demographic and economic research, where I looked at the economic history of the East End, sectors experiencing a decline and their causes, and develop potential ideas for the future that could help the Bangladeshi community to diversify their sources of business and employment and also help the general local enterprise scene to thrive. The local people in the area did not want to be pushed out by the encroaching City of London through big office developments and gentrification. This process of producing a local community-led community plan was seen to be a unique opportunity to prevent a community eviction and establish a sustainable future for local people live, work and thrive.

Planning for Real consultation at St Hilda’s Centre (1989)

It was during my work for the Community Development Group (CDG) that I first heard the name Bangla Town. I do not know the history of the idea and the name, when and how they emerged and who was the first person or group of people that came up with them first. There were many individuals who claimed to have conceived the idea first but all claims in this regard were mutually dismissed by rival claimants. Although other names were also suggested and talked about for a special zone in Brick Lane – such as Bangla Bazar, Sylhet Town, Little Sylhet – for some reason not known to me, the name Bangla Town resonated more with local Bangladeshis.

When I started to look at facts and figures things started to become clearer. One particularly important thing that I noticed was that the Bangladeshi population of the then Spitalfields Ward in 1989 was about 75% and, in Tower Hamlets, this community had the highest birth rate. This meant that in the coming years and decades the number and percentage of Tower Hamlets Bangladeshis would continue to increase if they did not move out of the borough in significant numbers. Further, as unlike in the 1970s and most of the 1980s when Brick Lane also had a stronger presence of non-Bangladeshis, such as Pakistanis and Indians, in terms of the ownership of shops, restaurants and factories, in the 1990s the area experienced a massive exodus of non-Bangladeshis and a corresponding increase in Bangladeshi run business, including restaurants, travel agents and groceries. Further, as by the end of the 1980s and during the beginning of the 1990s the Bangladeshi presence in the Brick Lane area became an overwhelming fact, both in terms of residency and business ownership, and also due to the long historical presence of the community in the area, it was natural and justifiable for such an idea – the establishment of Bangla Town – to emerge and capture the imagination of many.

Brick Lane Bangla Town (2004)

I personally never liked the name Bangla Town, which was borrowed from the name China Town. The name China Town and what it represents had developed over many centuries from the experiences of the Chinese Diaspora, primarily in lands controlled by the Europeans, including in overseas European settled colonies. That unique experience made the idea and reality of China Towns around the world something unique and special with respect to the Chinese Diaspora. I could not understand how a borrowed idea – developed through a long history of worldwide Chinese Diaspora experiences – could be successfully, sustainably and permanently planted and made to work in the context of the Bangladeshi community’s presence in London’s East End, an area with a long history of accommodating waves after waves of new immigrants, where they thrived and eventually moved out to pastures new.

London’s China Town (2004)

Second, I do not think that sufficient thoughts were put into the idea of Bangla Town before it was implemented through the renaming of the local ward and the establishment of an arch and several street lamps painted in Bangladesh flag colours. Alternative possibilities to the name Bangla Towns were not explored when considering how the Brick Lane area could be redesigned, redeveloped, rebranded and made attractive as a place of celebration of the long history of Bangladeshi presence that would provide imaginative ideas and frameworks for the community to showcase their cultures and traditions, along with others, in a thriving economic context.

Brick Lane Bangla Town (2004)

In the 1970s and 1980s, visiting China Town in London’s West End was a unique experience that made one feel that the London China Town was a special Chinese area. It attracted visitors from the normal Central London tourist trail as well as people directly coming to the area to visit the China Town. I did not think, based on the quality of discussion held on the Bangla Town idea and the economic and political power that Bangladeshis held, exercised, or could potentially acquire would be sufficient to achieve something high quality and sustainable as a Bangla Town. I was also very doubtful about the locational advantage and historical contexts of Brick Lane that would make the area conducive to establishing a successful ‘Bangla Town’.

In 1993 or 1994, I was invited to make a short presentation on the Bangla Town idea at the premises of Bangladeshi Welfare Association in Fournier Street, which was then run by Shofiqur Rahman Choudhury. The Association held an event to discuss local development and regeneration and the chief guest was Paddy Ashdown MP (Liberal Democrats). I was probably chosen to speak on the topic because of my previous work, in a limited capacity, on the local Community Plan; involvement in a small way in developing the Woolwich and Plumstead City Challenge bid in 1992 (unsuccessful) and with the Greenwich Waterfront Strategy. I was also involved at that time with a friend, Rumman Ahmed (Community Relations Advisor to the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea) in developing the concept of a Muslim Cultural Heritage Centre in Ladbroke Grove and some initial details, which were included in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea’s successful City Challenge bid in 1992.

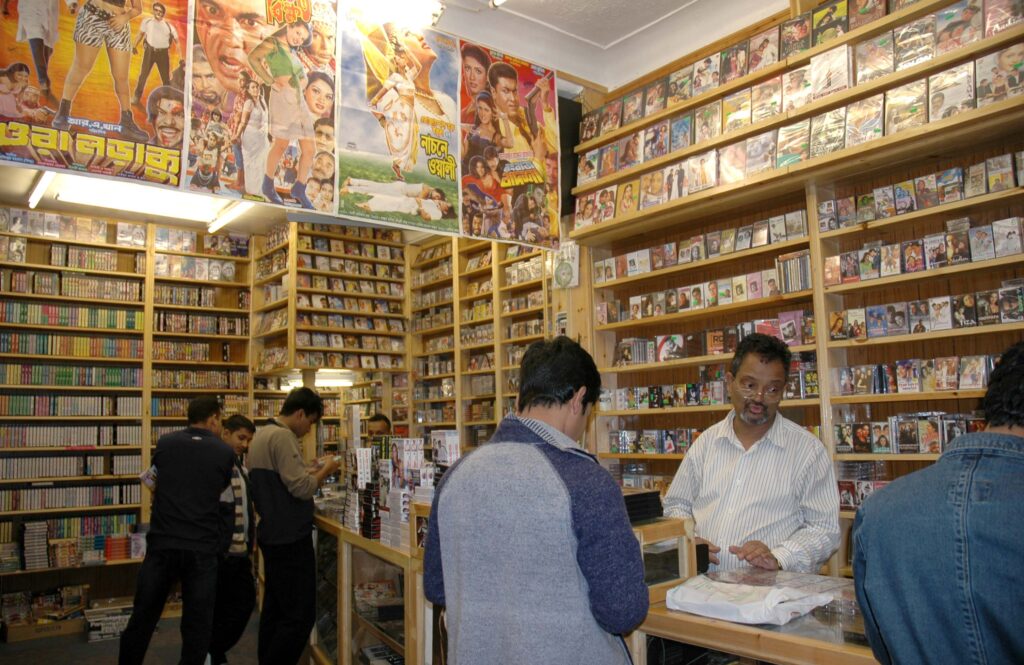

My involvement with Brick Lane goes back to 1974 when I first visited the area. At that time, I lived in Newham, which had very few Bangladeshis. Going to Brick Lane to eat samosas/kebabs in a café next to the Naz Cinema was a nice experience. I have also worked in the area for a few weeks at a time during my school holidays – in a large Jewish owned warehouse in Commercial Street, a Bangladeshi owned cash and carry also in the same road and an Indian Punjabi owned jeans factory near Petticoat Lane. Over many years, I played pool in the Seven Stars and snooker in a large snooker club with an entrance from Hanbury Street; prayed in Brick Lane Mosque, ate food in both Bangladeshi and Pakistani owned restaurants; bought Bangladeshi newspapers, music, grocery and sweets from many shops; and talked a lot of politics with many people.

Brick Lane Bangla Town (2004)

To my horror, when I first saw the tasteless quality of the Bangla Town concept given expression through some shoddy and unimaginative designs of the arch and streetlamps to represent the Brick Lane Bangla Town, I became speechless. I asked myself how could someone come up with something like this to represent something quintessential about Bengali/Bangladeshi culture/traditions that would be unique, aesthetically pleasing, aspirational and inspirational, be admired by a wide range of people and become the talk of the town. I wonder what kind of Bangla Town they had in mind, those who came up with such an awful design and colour scheme to signify the Bangla Town in Brick Lane.

Brick Lane Bangla Town (Bengal New Year Celebration 2006)