History of Bengal textiles until the East India Company destroyed the famous centuries-old industry

(Reproduced from a chapter that I contributed in ‘Bengal To Britain: Re-creating Historic Fashions of the Muslin Trade – by Stepney Community Trust)

Introduction

Present-day Bangladesh, particularly the Dhaka region, stretching from Mymensingh in the north to Barisal in the south, was for centuries the centre of the most prized and superfine hand-woven cotton textiles in the world. Foreign traders came from many places to purchase the highly regarded cotton textiles and silk that ordinary people in the region produced. Many outside travellers to the Bengal and textile buyers talked about the quality and reputation of Bengal textiles wherever they went and wrote about their experiences, often imagining mythical descriptions. Historical reports provide some knowledge about how the textile products of Bengal villages in history were highly valued, sought after and enjoyed by people in many parts of the world. J.J.A. Campus provides an example of the world-wide reputation of the historical woven fabrics is Bengal:

“There was a time when the muslins of Dacca shipped from Satgaon clad Roman ladies and when spices and other goods of Bengal that used to find their way to Rome through Egypt were very much appreciated there and fetched fabulous prices…” (History of the Portuguese in Bengal, (J. J. A. Campos)

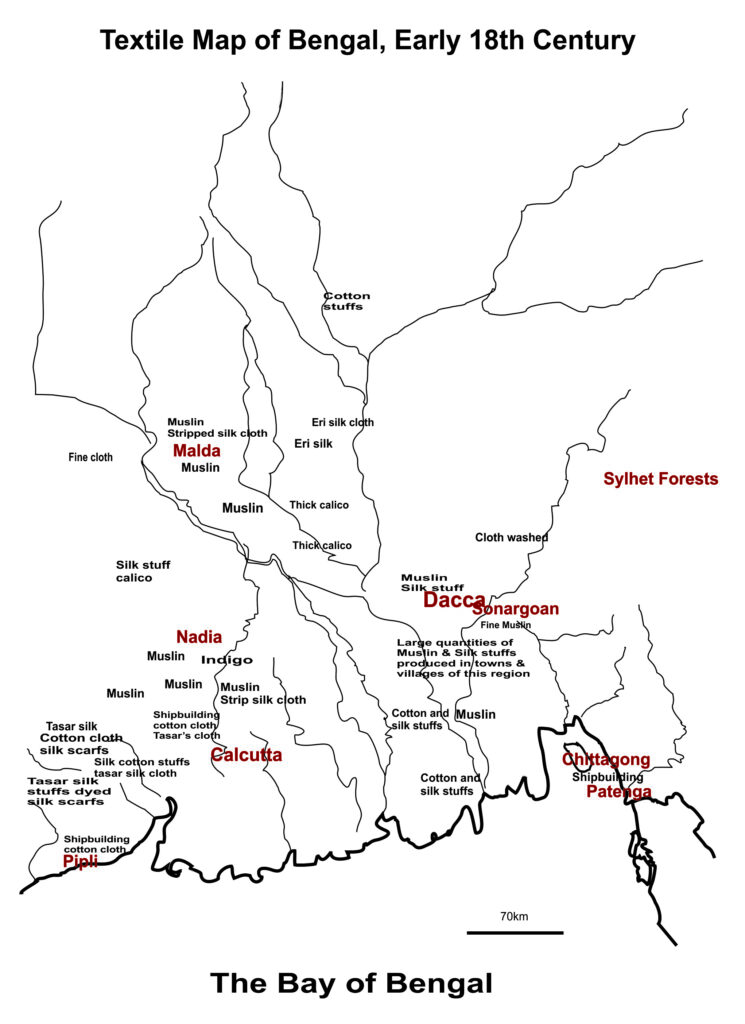

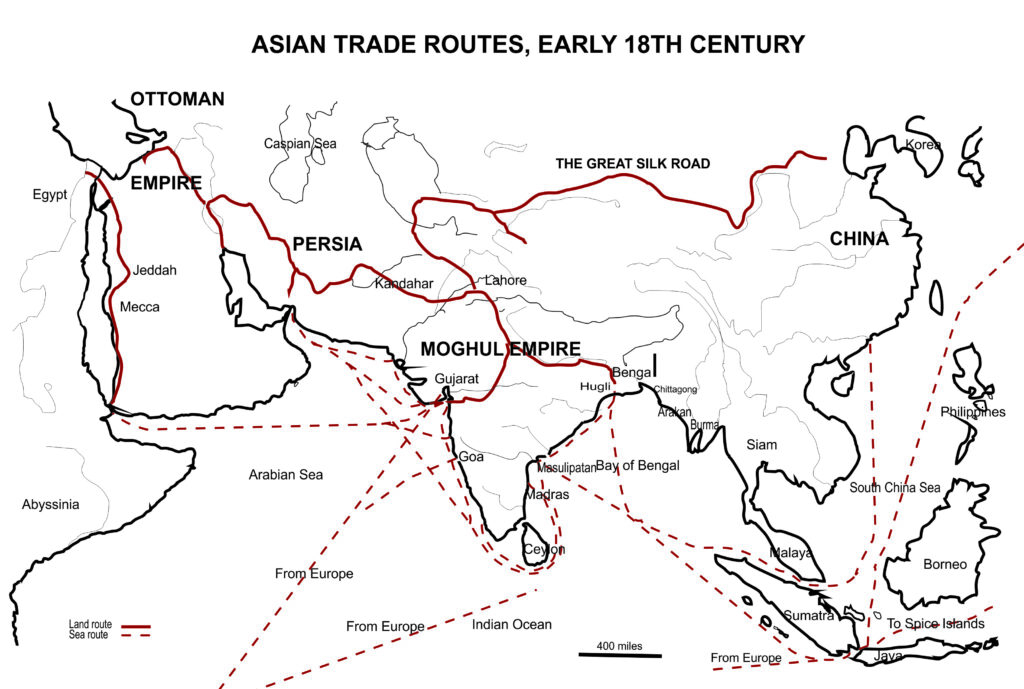

Based on a map by KN Chaudhuri (The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company: 1660-1760)

There were many types and varieties of textiles produced in the Bengal region – both for internal consumption and export – made from cotton, silk and mixed threads. Also, raw silk was an important export item of Bengal and at times constituted about a fifth of the total. Each type of woven textile had a wonderful name, often based on descriptions of beauty or aesthetic feelings experienced by human beings when interacting with nature. The types of items produced ran into hundreds, but some woven cotton fabrics were grouped due to some common characteristics and called muslin. The main characteristics shared by textiles called muslin were that they were made from very fine cotton threads, loosely woven and looked a bit transparent. Bengal was one of several textile export centres in India, each with its unique specialisations, supplying fabrics to the world.

The first Europeans to directly bring back textiles from Bengal and elsewhere in India were the Portuguese, from the early 1500s. The Dutch and the English joined the Indian Ocean trade from the early 1600s, but their textile trade mainly consisted, at first, of Inter-Asia trade where they bought Indian textiles to primarily exchange for Indonesian spices.

Until around the middle of the 17th Century, Britain was quite an uneventful place regarding clothing, textiles and fashion. This situation began to change however from the latter half of the century and did so quite rapidly and dramatically. India as a whole was the main source of that transformation, the first place being Gujarat, followed by Masulipatnam and Madras and then finally Bengal. The sea voyages by the English East India Company to Asia brought back spices, textiles, Chinese porcelain and other items to Britain that helped transform the country from a relatively dull place to something increasingly exciting. An indication of how that change was viewed at that time can be seen from Defoe’s Everybody’s Business is Nobody’s Business, where he observed that a ‘…plain country Joan is now turned into a fine London madam, can drink tea, take snuff, and carry herself as high as best. She must have a hoop too, as well as her mistress; and her poor scanty linsey-woolsey petticoat is changed into a good silk one, four or five yards wide as the least’. According to Niall Furguson, ‘In the seventeenth century, however, there was only one outlet the discerning English shopper would buy her clothes from. For sheer quality, Indian fabrics, designs, workmanship and technology were in a league of their own. When English merchants began to buy Indian silks and calicoes and bring them back home, the result was nothing less than a national make over.’ Every aspect of British life became entangled with things Indian. ‘In 1663 Pepys took his wife Elizabeth shopping in Cornhill, one of the most fashionable shopping districts of London, where, according to his words, ‘after many tryalls bought my wife a Chinke (chintz); that is, a paynted Indian Calico to line her new Study, which is very pretty’. When Pepy’s himself sat for the artist John Hayls he went to the trouble of hiring a fashionable Indian silk morning gown, or banyan. In 1664 over a quarter of a million pieces of calico were imported into England. There was almost as big a demand for Bengal silk, silk cloth tafetta and plain white cotton muslin. As Defoe recalled in the Weekly Review of 31 January 1708: ‘It crept into our houses, our closers, our bedchambers; curtains, cushion, chairs, and at last beds themselves were nothing but Calicoes or Indian stuffs.’ (Empires: How Britain made the modern world, Niall Furguson).

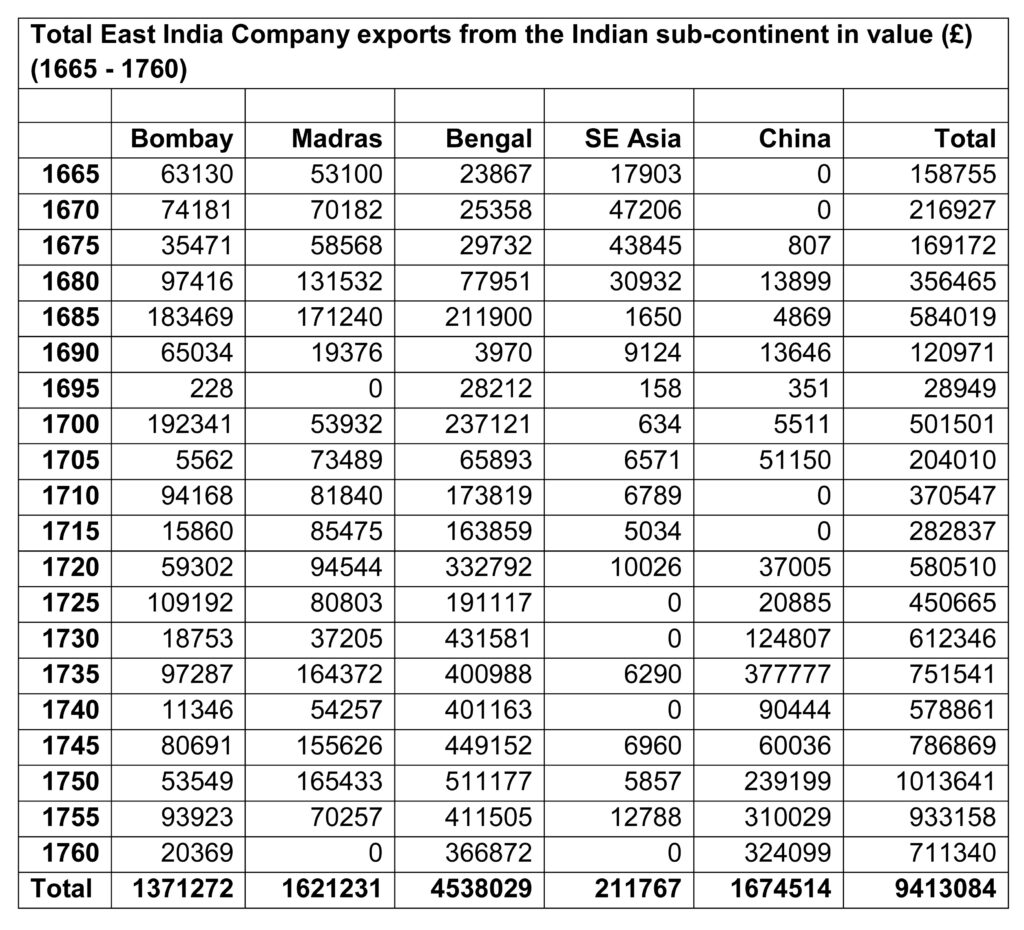

The first place that the East India Company visited in the Indian subcontinent was Gujarat in 1608, primarily to buy Indian textiles to exchange for spices from the Indonesian spice islands. For about three decades this was the main source from where the Company purchased most of its Indian textiles. Then from the late 1630s, when the Company established a base in Madras in South India, another important centre was added to its sources of textiles. The third centre, which subsequently became the most important was Bengal, where the company started to purchase textiles in large quantity from around the mid-17th Century. At first, the Bengal element was very low but gradually increased to become the main provider of the East India Company’s textile needs. By 1725 Bengal’s contribution to East India Company’s textile export was bigger than the other two centres combined and this continued throughout the 18th century. This means that a significant amount of Indian textiles that came to Britain were from Bengal.

Although the British imported large quantities of textiles from Bengal between the latter part of the 17th century and throughout the 18th century there exist very little physical evidence of how they were used in fashion in the early days. However, many fashionable ladies items from the later Regency period (1790-1820), made from Indian muslins, still survive in museums and collections around the UK and beyond. This was also the period when Jane Austen was writing her famous novels and enjoying fashion items made from muslins, which means there is an additional heritage interest concerning the historical Bengal textiles.

‘By the late 18th Century Indian textiles were the height of fashion. In 1814 alone over 1.25 million Indian cloths were exported to Britain. The Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities explains how they were put to use. For example, we are told that Indian Muslin, a lightweight cotton, was used for “ruffles, cravats and handkerchiefs but also gowns and ladies dresses ”. This shows that both men and women wore Indian muslins, although women seem to have done that in larger quantities. Muslin is also detailed in the newspapers, like on 3rd August 1821, The Guardian describes a dress constructed from four different types of muslins. It is therefore clear that Indian fabrics, like muslin, were highly fashionable.’ (HIST2530 Indian Influences in Regency British Dress, LeedsWIKI).

Besides the consumption of large quantities of Indian fabrics in UK fashion and many other everyday usages, the varieties of textiles imported by the East India Company also became a valuable trade currency. Some of the textile items brought to the UK were for consumption, while others were re-exported to many places around the world, including for the purchase of African slaves. Although it is clear that most of the re-export textiles to Africa originated in Gujarat or some from Madras, the sheer volume and percentage of the total textiles imported from Bengal alone mean that British re-export of Indian textiles to Africa must have included an element that also originated in Bengal. For example, it is known that between 30-40% of Indian textiles imported by the East India company was re-exported to Africa during 1720-1740.

From figures provided by Bhishnupriya Gupta on the number of textile piece goods from India and by KN Chaudhury on the total value of exports from Asia by the East India Company, it is clear that the vast majority of the textiles were from Bengal. According to Bhishnupriya Gupta, of the 3,130,000 pieces of Indian textiles imported by Britain from India, during the twenty years in question, 2,066,000 (66%) came from Bengal. In terms of value, during the same period, KN Chaudhuri put Bengal’s share of East India Company’s exports from India to be around 70%. Further, according to Prasannan Parthasarathi, during that time, ‘Indian textiles accounted for about a third of British exports to Africa. From the 1740s, Indian cloth represented a smaller fraction of British exports, but the quantity of Indian textiles sold in west Africa exploded because of the tremendous expansion in the slave trade in the second half of the eighteenth century’ (The European Response to India Cottons). This means that there is a slave connection to textiles produced by Bengal weavers, although the proportion of textiles that came from western India that were re-exported to Africa were no doubt higher than Bengal textiles.

Bengals’ legendary reputation

First England and then Britain became increasingly familiar with Bengal from the latter part of the 17th Century primarily through the imports of its textiles. However, the region was already a well-known place around the world for its fine weaving, particularly cotton, and rich textile history. The tradition of high-quality fabrics making goes back to ancient times and there are records of textiles of these regions being exported to Rome event before Christ was even born, especially muslin fabrics. This story is not known very well or appreciated now, either in Bengal/Bangladesh or outside the Indian subcontinent. According to Campus, ‘There were times when the muslins of Dacca shipped from Satgaon clad Roman ladies and when spices and other goods of Bengal that used to find their way to Rome through Egypt were very much appreciated there and fetched fabulous prices.'(History of the Portuguese in Bengal, by J.J.A. Campus). Many ancient and past travellers to the land had written accounts of the quality, variety and fame of Bengal and its textiles. Following are some examples of historical reports of Bengal textiles, particularly of the fine muslin varieties:

“The Provinces of Bengala are very extensive and are much frequented by foreigners, owing to the trade there, both in food-stuffs, as I have remarked above, as also in fine cloth. So extensive is the trade that over one hundred vassals are yearly loaded up in ports of Bengala with only rice, sugar, fats, oils, wax, and other similar articles. Most of the cloth is made of cotton and manufactured with delicacy and propriety not met with elsewhere.

The finest and richest muslins are produced in this country, from fifty to sixty yards long and seven to eight handbreadths (22/2) wide, with borders of gold and silver or coloured silks. So fine, indeed, are these muslins that merchants place them in hollow bambus, about two spans long, and, thus secured, carry them through Corazane, Persia, Turkey, and many other countries.” Travels of Fray Sebastian Manrique (1629-1643)

“It was also about this time (Dharmapala) (775-812 AD), too, that a regional economy began to emerge in Bengal. In 851 the Arab Geographer Ibn Khurdadhbih wrote that he personally seen samples of the cotton textiles produced in Pala domains, which he praised for their unparalleled beauty and fineness.

As early as 1415 we hear of Chinese trade missions bringing gold and silver into the delta, addition to satins, silks, and porcelain. A decade later another Chinese visitor remarked that long-distance merchants in Bengal settle their accounts with tankas. The pattern continued throughout the next century. “Silver and Gold”, wrote the Venetian traveller Cesare Fedeci in 1569, “from Pegu (Burma) they carried to Bengala, and no other kind of Merchandize.” The monetization of Bengal’s economy and its integration with markets throughout the Indian Ocean greatly stimulated the region’s export-manufacturing sector.

Although textiles were already prominent among locally manufactured goods at the dawn of the Muslim encounter in the tenth century, the volume and variety of textiles produced and exported increased dramatically after the conquest. In the late thirteenth century, Marco Polo noted the commercial importance of Bengali cotton, and in 1345 Ibn Battuta admired the fine muslin cloth he found there. Between 1415 and 1432 Chinese diplomats wrote of Bengal’s production of fine cotton cloths (muslins), rugs, veils of various colors, gauzes (pers., chana-baf), material for turbans, embroidered silk, and brocaded taffetas.

A century later Ludovico di Verthema, who was in Gaur between 1503 and 1508, noted: “Fifty ships are laden every year in this place with cotton and silk stuffs… These same stuffs go through all Turkey, through Syria, through Persia, through Arabia Felix, through Ethiopia, and through all India”. A few years later Tome Pires described the export of Bengali textiles to ports in eastern half of the Indian Ocean. Clearly, Bengal had become a major centre of Asian trade and manufacture.” (The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, Richard M. Eaton).

“There was a time when the muslins of Dacca shipped from Satgaon clad Roman ladies and when spices and other goods of Bengal that used to find their way to Rome through Egypt were very much appreciated there and fetched fabulous prices…

Regarding the trade and wealth of Bengal, the Portuguese had the most sanguine expectations which did not, indeed, prove to be far from true. Vasco de Gama had already in 1498 taken to Portugal the following information: “Bengala has a Moorish King and a mixed population of Christians and Moors. Its army may be about twenty-four thousand strong, ten thousand being cavalry, and the rest infantry, with four hundred war elephants. The country could export quantities of wheat and very valuable cotton goods. Cloths which sell on the spot for twenty-two shillings and six pence fetch ninety shillings in Calicut. It abounds in silver”.

From time to time Albuquerque had written to King Manoel about the vast possibilities of trade and commerce in Bengal. When the Portuguese actually established commercial relations in Bengal, they realised to their satisfaction what a mine of wealth they had found. Very appropriately, indeed, did the Mughuls style Bengal, “the Paradise of India”…

The Portuguese shipped various things from Bengal, seat as it was of a great many industries and manufactures. Pyrard de Laval who travelled to Bengal in the beginning of the 17th century says, “The inhabitants (of Bengal), both men and women, are wonderously adroit in all such manufactures such as of cotton, cloth and silks and in needlework, such as embroideries which are worked so skilfully, down to the smallest stitches that nothing prettier is to be seen anywhere.” The natural products of Bengal were also abundant, and various are the travellers who have dwelt on the fertility of the soil of Bengal watered as it is by the holy Ganges…

Dacca was then the Gangetic Emporium of trade. It was there that those priceless muslins were made even as early as the Roman days. Its thread was so delicate that it could hardly be discerned by the eye. Tavernier mentions, “Muhammad Ali Beg when returning to Persia from his embassy to India presented Cha Shafi III with a cocoanut of the size of an ostrich egg, enriched with precious stones, and when it was opened a turban was drawn from it 60 cubits in length, and of muslin so fine that you would scarcely know what it was had in your hand.”

These muslins were made fifty and sixty yards in length and two yards in breadth and the extremities were embroidered in gold, silver and coloured silk. The (Moghul) Emperor appointed a supervisor in Dhaka to see that the richest muslins and other varieties of cloth did not find their way anywhere else except to the Court of Delhi. Strain on the weavers’ eye was so great that only sixteen and thirty years old people were engaged to weave. There are the men who with their simple instruments produced those far-famed muslins that no scientific appliances of civilized times could have turned out.” History of the Portuguese in Bengal (J. J. A. Campos).

Key players, routes and products of Bengal trade

India as a whole has a very long and rich history of producing and trading in amazing varieties of textiles, including cotton and silk, both plain and with designs. Plain fabrics were of many varieties also, ranging from highly fine and transparent muslin to coarse materials for ships’ sails. The designed items were made from design woven during the weaving process to painting and block printing. Although all regions and areas in India produced a variety of textiles, cotton-based fabrics were its most prized items and the Indian subcontinent was the dominant producer in this regards for centuries. According to Prasannan Parthasarathi and Giorgio Riello, during 1200-1800 AD, ‘the bulk of the cottons that crisscrossed the globe had their orgins in the Indian subcontinent, which was the pre-eminent centre for cotton manufacturing in the world until the nineteenth century’ (The Spinning World: A Global History of Cotton Textiles, 1200-1850, Giorgio Riello and Prasannan Parthasarathi).

All places in India, especially urbanised locations, had centres of textile production. Most producing areas catered for the needs of ordinary people, rulers, elite groups, business people, government officials, army, etc. However, certain, locations and regions within the Indian sub-continent developed many types of specialisations in textile production and over time evolved into large exporting areas (Bengal, Gujarat, Masulipatam and Punjab). Most of Punjab’s textiles exports went to western and central Asia through land routes while a large proportion of the other three regions’ textiles were exported by sea to various locations in the Middle East, Africa and South-East Asia. Further, from the Middle East, many Indian textiles were taken to various locations in Europe. However, after the arrival of the Portuguese to India in the late 15th century a small amount of textiles from there started to travel directly to Europe, which rapidly started to increase after the Dutch and the British joined in the Indian Ocean trade from early 17th Century. Some aspects of Bengal’s international trade can be seen from the following:

“It is well-known… that so far as Bengal’s International trade was concerned, the huge demand for its commodities in the global markets, especially its textiles and raw silk, attracted buyers from various parts of the world. As Bengal during this period (1650-1757) was self-sufficient and as the market for import commodities was strictly limited, almost all these traders, whether Europeans or Asians, had to bring in precious metals, mostly silver, to Bengal for the procurement of the export commodities. Thus the influx of silver to Bengal in the seventeenth and the early half of the eighteenth century was because of Bengal’s favourable balance of trade with the rest of the world. (European Trade, Influx of Silver and Prices in Bengal (1650 – 1757) (Sushil Chaudhury)

In addition to exporting Indian textiles abroad, the Indian subcontinent had thriving inter-regional and mutually dependent trade. For example, Gujarat had a thriving silk manufacturing industry, producing beautiful varieties of silk textiles, but most of the raw silk for this came from Bengal. On the other hand, demand for Bengal’s cotton textiles was so great that the local production of raw cotton was insufficient to meet the amount needed so a large quantity of Gujarat raw cotton was imported each year into Bengal. Gujarat cotton was however not very fine and could not be used to produce the top quality muslins. They were instead used to manufacture coarser materials.

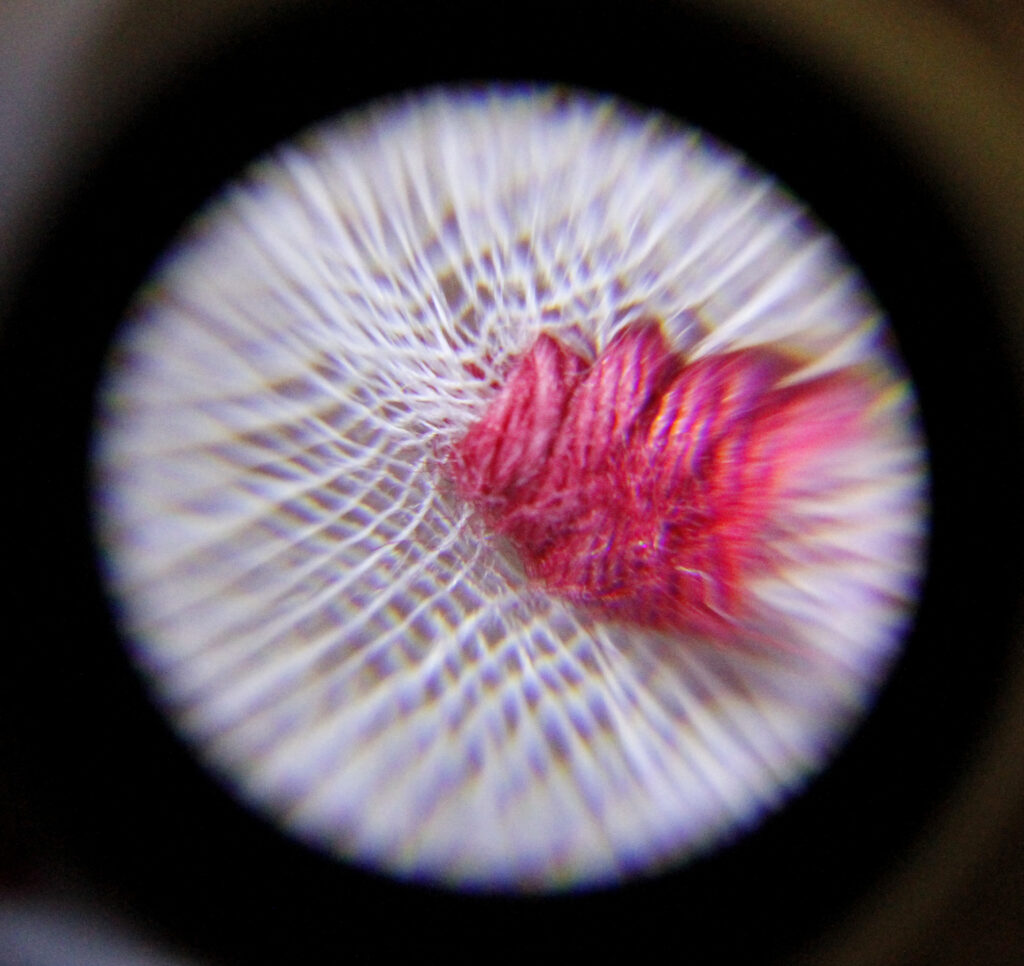

The high-quality fine textiles that came to be known as muslin were primarily manufactured by raw cotton grown in East Bengal within a narrow strip of land along the Brahmaputra river from Meymansingh to Barisal. The fine textiles produced by this cotton became known as Dhakaya Muslin. It was Dhaka region’s native cotton that was said to be both soft and strong at the same time, which produced muslins: the famous textiles of Bengal. The quality of the soil, high levels of rain and the local environmental factors all contributed to helping evolve the legendary muslin cotton plant and the local people developed specialised skills to produce superfine threads from which beautiful textiles were woven with their hands.

For a very long time, Bengal had a thriving direct sea-borne and land routes based trade with many parts of the world and its manufactured textiles also reached near and far away places through indirect routes and second-hand trade. The Indian Ocean was very busy with ships and boats taking goods to and from many locations, along long-established trading routes. When the Portuguese first arrived in the Indian Ocean on the eve of the 16th Century, they began to destroy and change the old trading networks and the operations of the long-established trading systems involving Africa, Middle East, India, South-East Asian and China. The process got speeded up after the Dutch and English established their trade in the India Ocean from early 17th century onwards. Information about the ancient trade of India, including that of Bengal) has been written by many past travellers.

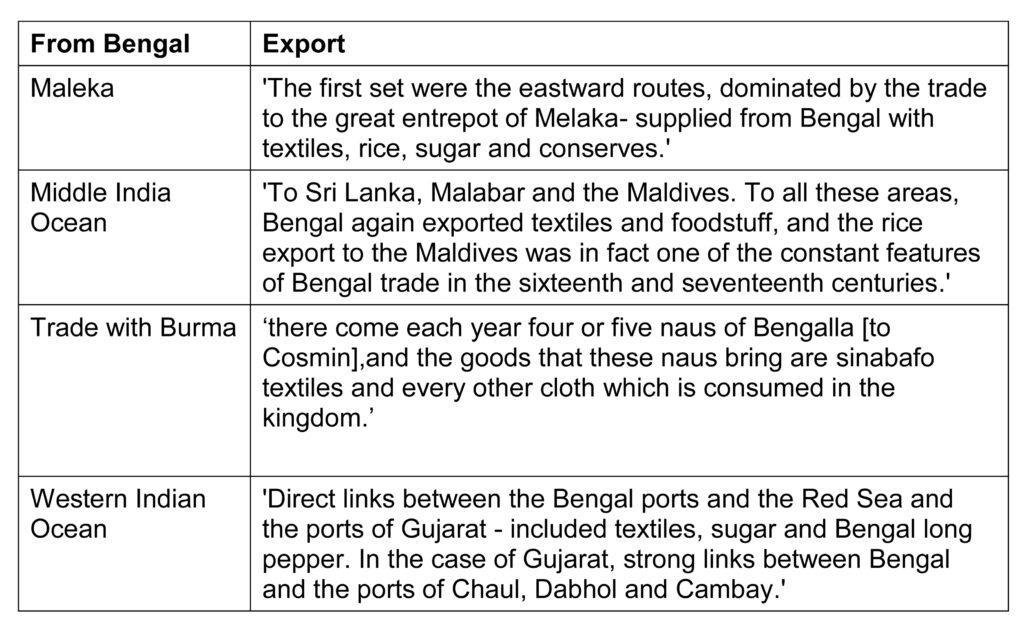

According to Tom Pires, a Portughese traveller during the early 16th Century, ‘A junk (four or five ships) goes from Bengal to Malacca once a year and sometimes twice. Each of these carries from eighty to ninety thousand cruzados worth. They bring fine cloths, seven kinds of sinbafos, three kinds of chautares, beatilhas, beirames and other rich materials… cut-cloth work in all colours and very beautiful… Bengal cloth fetches as high price in Malacca, because it is a merchandise all over the East’ (Pires, Suma Oriental). Sanjay Subramanyan recently wrote on Bengal’s sea-born trade during the 16th Century. In the ‘Notes on 16th Century Bay of Bengal Trade‘ he provides information and details of Bengal’s trade with Burma, Malaka, Sri Lanka, Maltives, Gujarat and the Middle East. A variety of goods were imported and exported, and textiles of Bengal were a very important element of its total exports. ‘… by the early sixteenth century, the Bengal region was a major exporter of textiles to many regions in Asia, a distinction it shared with two other parts of India: namely, Coromandel and Gujarat… Bengal was celebrated, however, not merely for its textiles… the region was a considerable exporter of grain (particularly rice)… which were carried to a diversity of destinations. Bengal was also known for its production and export of sugar…’

According to Sanjay Subramanyam, Bengal’s seaborne trade mainly consisted of four routes. The table below provides details of Bengal’s exports to many locations, which includes textiles.

India as a whole has a very long and rich history of producing and trading in incredible varieties of textiles, including cotton and silk, with and without designs. Undesigned fabrics were of many types, ranging from highly fine and transparent muslin to coarse materials for ships’ sails. The designed items were produced by incorporating a process during the weaving process or painting and block printing on plain fabrics. Although all regions and areas in India produced a variety of textiles, cotton-based fabrics were its most prized items and the Indian subcontinent was the dominant producer in this regards for centuries.

After the Europeans entered direct trade with India and Asia, Europe became another destination for Bengal’s exports, particularly textiles. In this regard, the Dutch and English were the biggest trading partners. At first, the Dutch imports from Bengal were larger but from around the first quarter the of the 18th Century the English established a position of dominance which remained and continued to grow until they finally took control over Bengal after the Battle of Plassey in 1757. From then on the British virtually monopolised Bengal’s textile trade and squeezed other traders, both Europeans and Asians, out of the region.

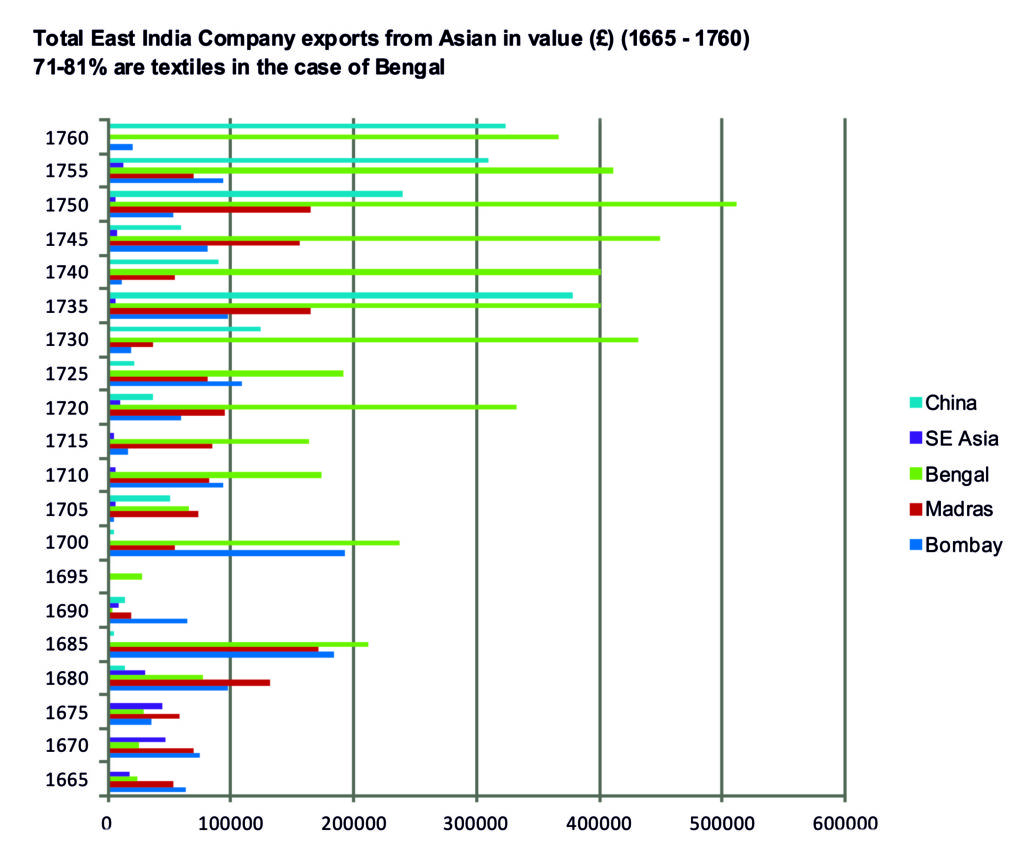

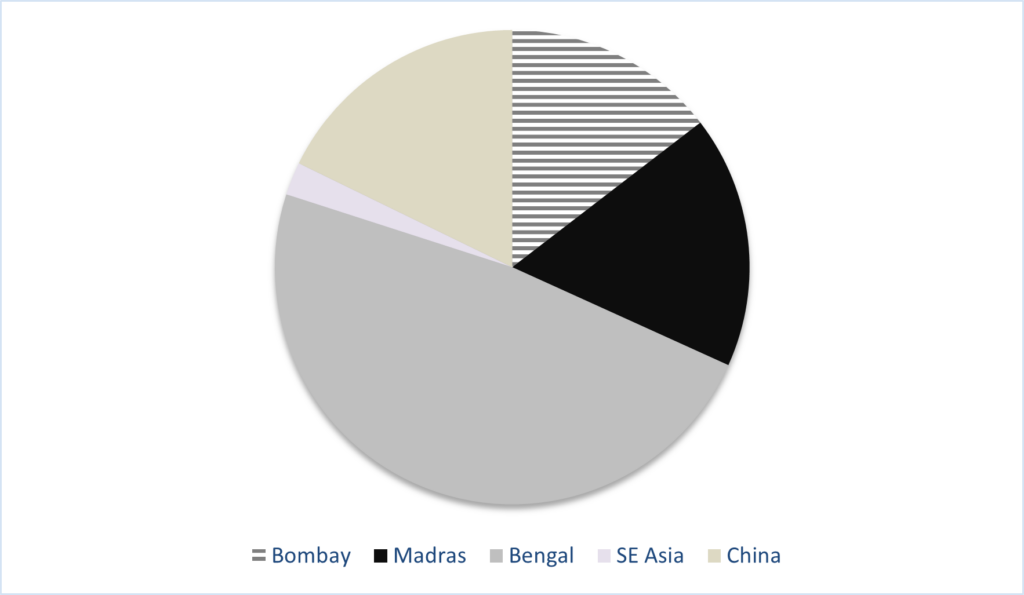

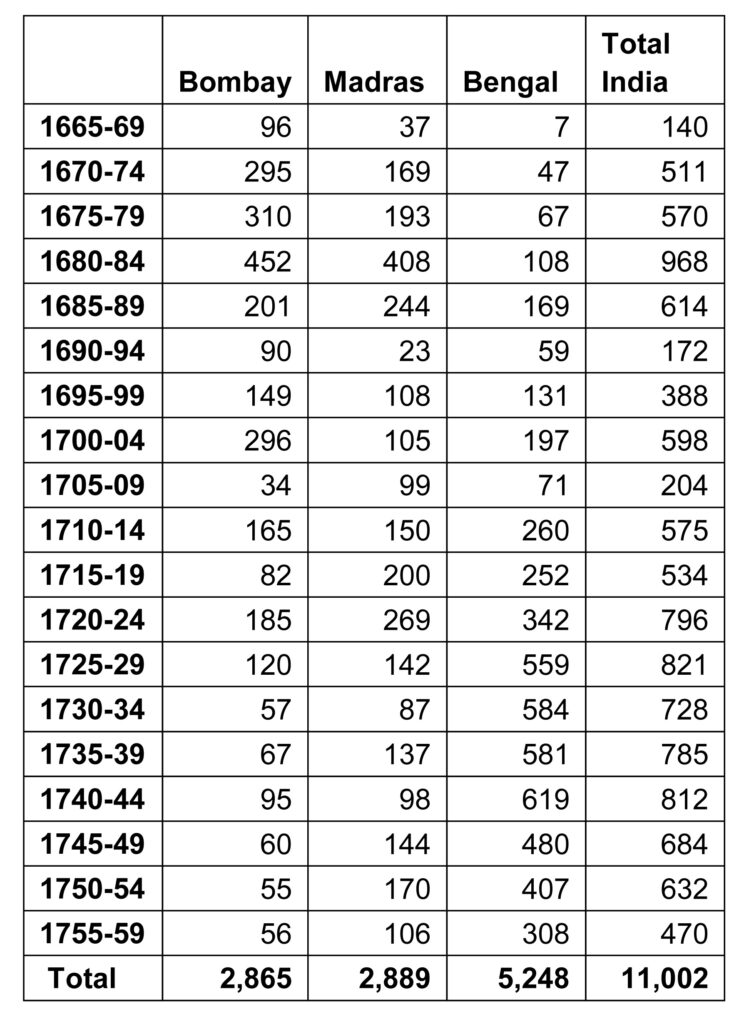

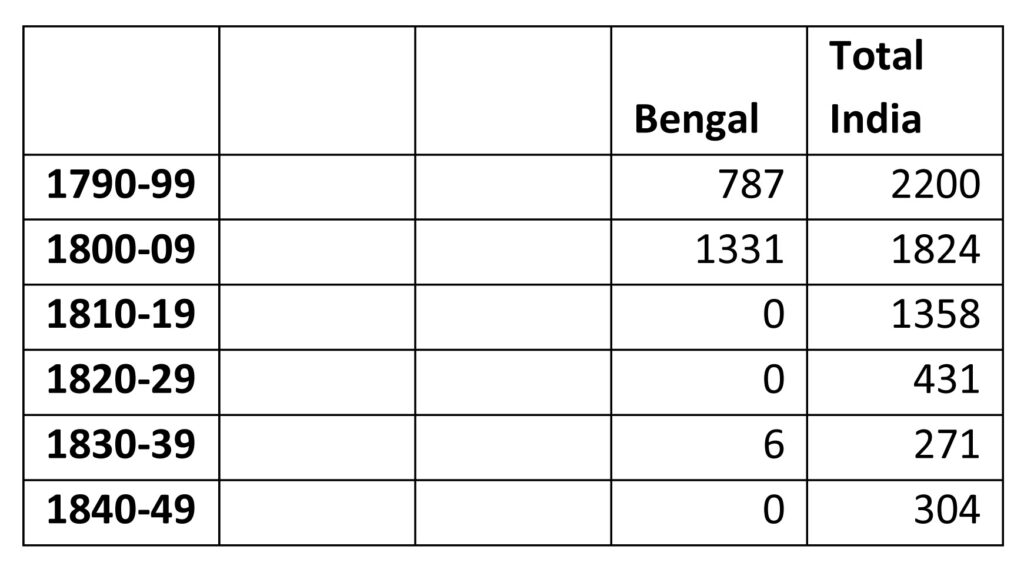

Two tables and graphs are provided below to show the scale of British imports of goods from Asia and India and Bengal’s share. The first is on the total value, based on five-yearly intervals, between 1665 and 1760, developed from annual figures generated by KN Chaudhuri. Textiles were about 71-81% of the total value of goods imported from Bengal to the UK by the East India Company. The second, based on the work of Bhishnupriya Gupta, shows the number of items of textiles imported by the British from the Indian subcontinent during 1665-1849 and Bengal’s total share. Both the tables and associated graphs show that from around the end of the first quarter of the 18th Century Bengal’s share of total exports of textiles from Asia by the British was higher than all other locations combined.

The above table based on data provided by KN Chaudhuri (The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company: 1660-1760)

From various other sources, it has been established that around 71-81% of the total imports were textiles in the case of Bengal

The followings are from Bhishnupriya Gupta’s study, based the work of several others. (Competition and control in the market for textiles: The weavers and the East India Company).

Bengal

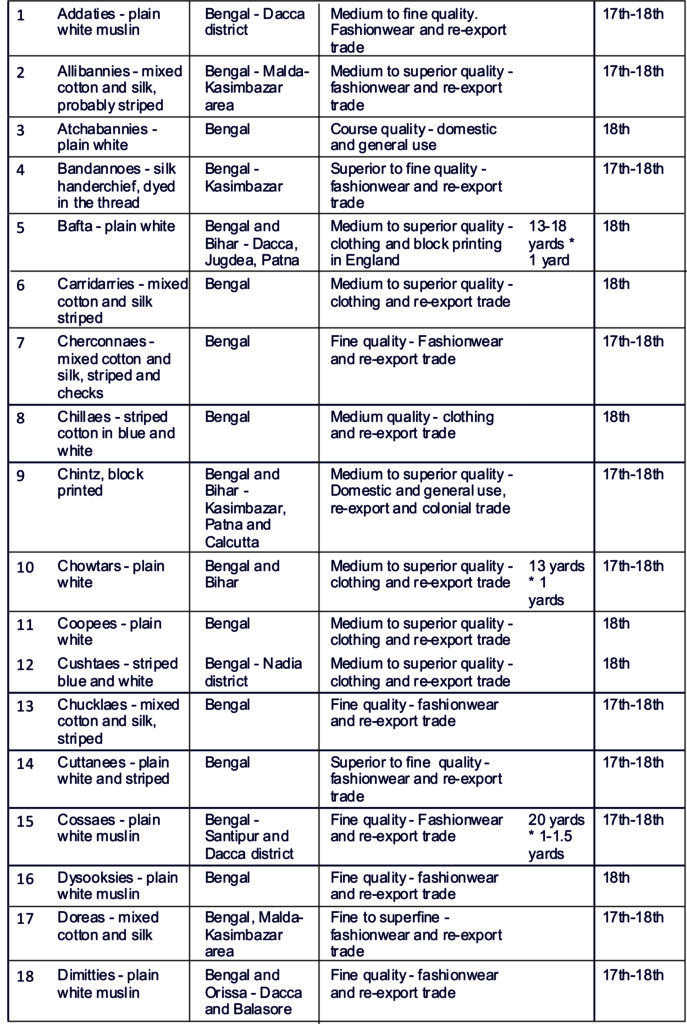

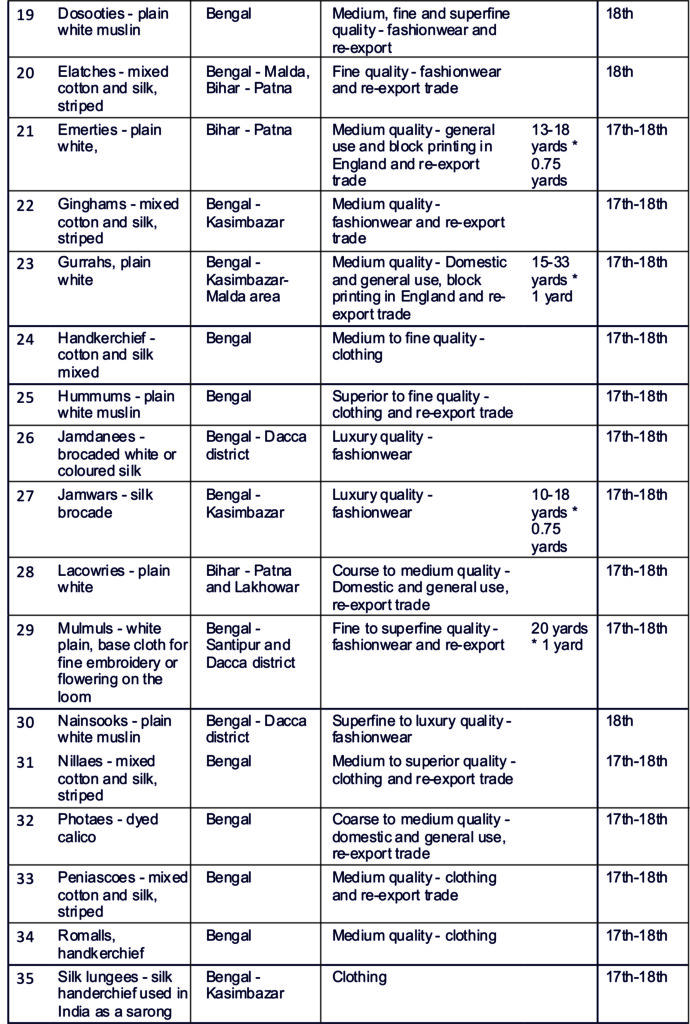

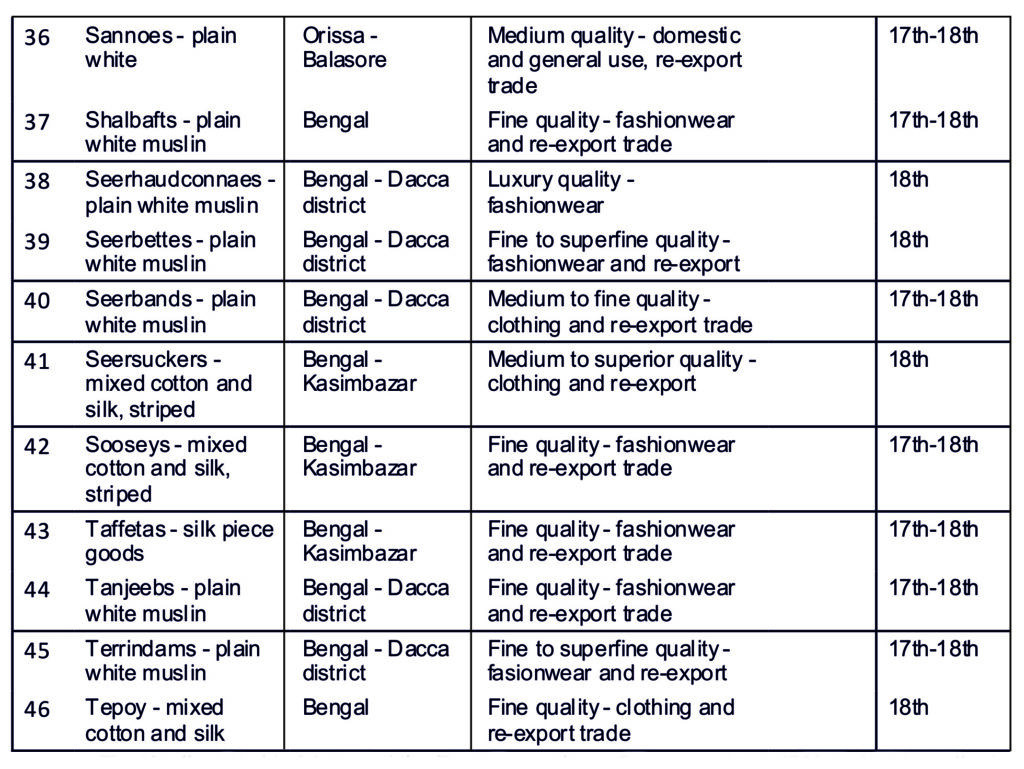

Various locations within Bengal developed their own specialisations in the production of textiles. The Dhaka region in present-day Bangladesh became famous for its fine muslins, although the area also produced a range of other textiles. In West Bengal, the main locations for textile production were Hugli, Kasimbazar and Malda, where they also produced muslins. Most of the fine and luxury quality muslins exported by the East India company to Europe were from the Dhaka region. According to East India Company records they were in their Anglicised names: Addadies, Cossaes, Dimitties, Jamdanees, Mulmuls, Nainsooks, Seerbands, Seerbettes, Shalbafts, Tanjeebs and Terrindams. The table below lists the most frequently exported textiles by the East India Company from different locations within Bengal.

East India Company’s Textile Imports from India to Britain (1665-1760)

The above table is based on information from The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company: 1660-1760 by KN Chaudhuri.

During the Ottoman Empire, traders also bought a large quantity of Dhaka muslins for export to Turkey and Persia. Besides the Moghuls in Delhi and Agra, in many other areas in Asia where the luxurious textiles of Bengal were consumed and highly valued. During the Moghul rule, muslins were among the top quality Indian textiles consumed by the rulers, their families, noblemen, etc. Moghuls also helped expand and develop deeper connections between different Indian regions under their rule and beyond to increase trade and, as a result, government revenue.

The arrival of the Europeans injected new demands and creativity within the various textile exporting regions in India. According to Sushil Chaudhury, this new factor helped increase Bengal’s textiles production by around 33%, which generated additional economic development and created many local jobs.

“The textile export by Asian merchants can be computed at around Rs 9 million to Rs 10 million a year, while the total exports of Bengal textiles by the Europeans did not exceed Rs 5 or 6 million. While the total value of silk exported by the Asian merchants is estimated at around Rs 5.5 million on an average during the period from 1749 to 1753, and Rs 4.1 million from 1754 to 1758, the average annual value of the European export of silk was only around Rs 0.98 million over the same period. In other words, the Asian share of silk exports from Bengal was 4 to 5 times more than the European share in the pre-Plassey period.” (The Prelude to Empire, Sushil Chaudhury).

The following map, based on a map in ‘The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company: 1660-1760’ by KN Chaudhuri, shows the Asian trading routes and how the Indian subcontinent was connected with the outside world during the early 18th century. Bengal was connected with many places in India, Asia and Europe, by land and sea, including the inland trading world of the Great Silk Road, Persia, Ottoman Empire and Arabia.

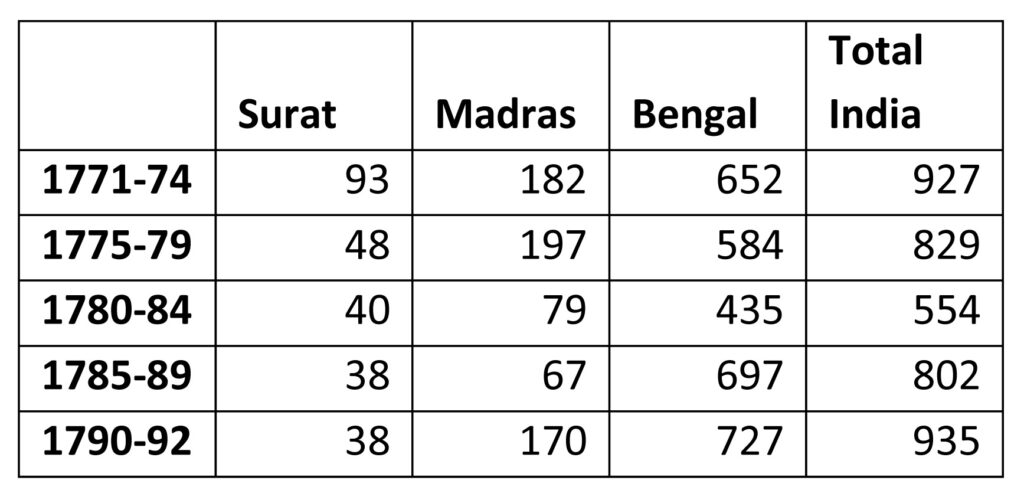

The decline of trade and techniques

During its long history, several factors, including the changes in political and dynastic situations, caused the demand and taste for Bengal textiles to vary from time to time. New markets and new geographical locations around the world were added and sometimes lost. For example, during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries Europeans directly shipped Bengal textiles to Europe and elsewhere – this was relatively small during the 15th hundreds, which was primarily carried out by the Portuguese. The main destinations for the Portuguese export of Bengal goods, including textiles, were the various ports in Asia, some of which they controlled directly, such as Maleka and Goa, and others like Sumatra, Borneo, Maldives, China and Japan with which they traded. After the British took over of Bengal in 1757, the new power in charge slowly squeezed out most of the foreign buyers of Bengal textiles from the region, thus significantly reducing Bengal’s trading links with the outside world. By the end of the 18th century, there was very little direct exports of Bengal textiles by parties other than the British (East India Company and private traders) and their local partners.

Soon after the British conquest of Bengal, the East India Company stopped paying for their textile purchases using cash brought in from Britain. Instead, they switched to using revenues they collected from Bengal taxes to purchase Bengal textiles. They also made life difficult and near impossible for other countries to trade with Bengal. In effect, they cut off or reduced Bengal’s independent trading links with traditional trading partners and monopolised the buying of textiles, imposed conditions and forcibly lowered prices that they paid to weavers to purchase textiles.

“From the final decade of the eighteenth century, cloth exports from South Asia had already begun to decline for a variety of reasons, including the monopsony that the English East India Company had built in Bengal and South India, which blocked many buyers from obtaining cloth.”

(Cotton Textile Exports from the Indian Subcontinent, 1680-1780, Prasannan Parthasarathi)

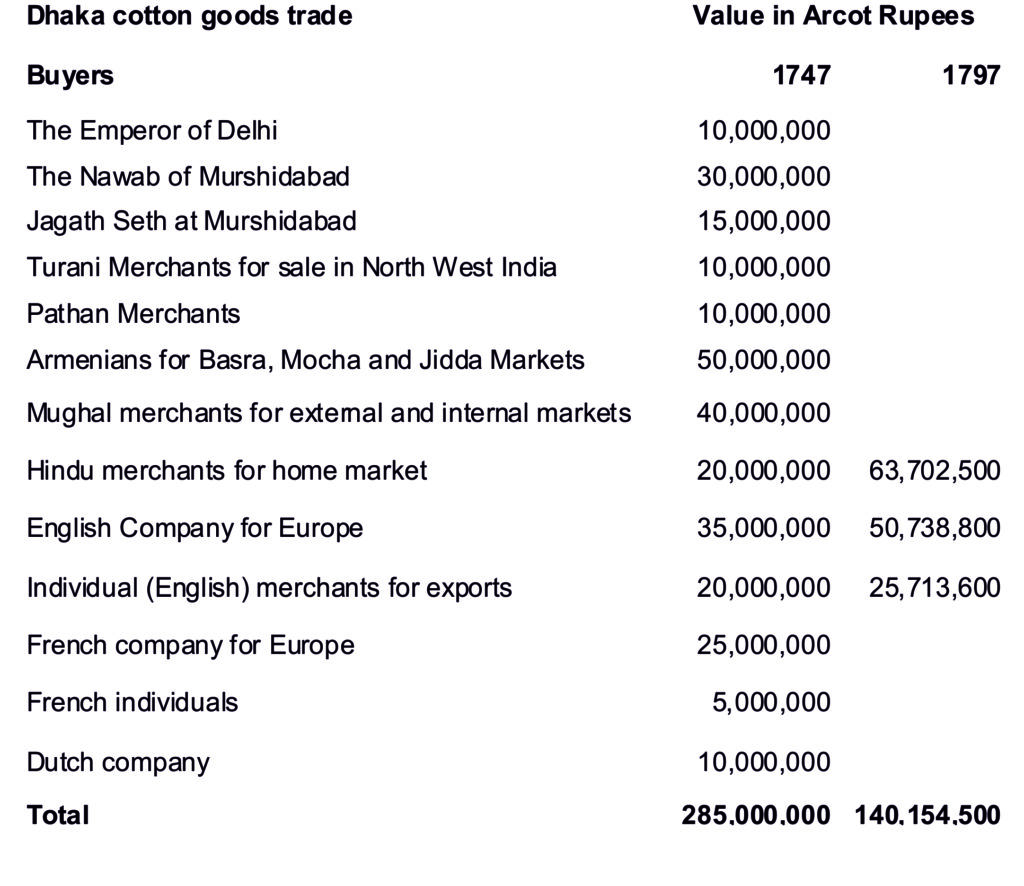

The following table shows what happened to Dhaka cotton trade during the first forty years of British rule after the East India Company’s conquest of Bengal. In 1747, ten years before the Battle of Plassey in 1757, there were about thirteen main destinations for cotton exports, which generated 285,000,000 in Arcot Rupees. Fifty years later in 1797, there were only three types of buyers left, which caused the total value of Dhaka cotton exports to reduce to 140,154,500 in Arcot Rupees. This is less than half of what it was fifty years earlier. Evidence suggests that as the East India Company squeezed more out of the weavers, more textiles for less money, through their monopoly and domination of the market, the reduction of the monetary value into half does not mean that the quantify was also reduced proportionately.

Mohsin, K.M., Commercial and Industrial Aspects of Dhaka in the Eighteenth Century, Dhaka: Past Present Future, edited by Sharif Uddin Ahmed

Soon afterwards the declining state of Bengal textiles manufacturing experienced another massive shock which ultimately brought the extraordinary history of the region’s fabric manufacturing to something quite insignificant. This was caused by the industrial revolution that started in England and the East India Company’s flooding of the captured Bengal market with cheaper machine-made cotton goods from Britain. The Bengal textile industry then declined rapidly and by around the 1850s, there was hardly anything left of its past glory. These factors caused the once-famous textiles industry of Bengal to demise, causing the death of the legendary fine muslin textiles. Muslin was Bengal’s finest heritage that made the region famous and attracted visitors and riches to its shores for millennia.

The fine muslin textiles were produced by a special cotton variety, native to the region around Dhaka, but now no known trace of that plant exists. What makes the situation even worse is the thought that the cotton plant/tree that produced the soft and strong threads for hand-weaving the amazingly fine and beautiful muslin fabrics may have become extinct.

The Revival

After a long period of decline, the situation is now experiencing a slow positive change and there seems to be an increasing interest in the history of Bengal textiles. This is due to the efforts being made by dedicated individuals and groups involved in research and practical work. These attempts are helping to revive and promote many lost techniques and traditional methods of textile production. They are trying to help make visible the rich history of the once famous textile industry of Bengal. The aim is to achieve a wider appreciation of this textile heritage and, through an increase in interest, help bring back its many lost traditions and prevent knowledge and skills currently under threat from disappearing.

Through theoretical and practical efforts the rich history of Bengal textiles is slowly finding its way to the wider consciousness of people around the world, particularly in Bangladesh and West Bengal in India. This trend is set to grow as a result of current interest and also spurred by new discoveries. An example of a chance discovery is the recent unearthing of several publications on costumes. According to Madhumita Bose, ‘two series of volumes… dating back to 1866, titled, Textile Manufactures and Costumes of the People of India‘, which are ‘rare volumes of intricate designs and weaving techniques’, were stumbled upon ‘while breaking open a locked cupboard’. The volume was produced by the British who used British locks to shut the cupboard, which is situated at the Industrial section of the Indian Museum in Calcutta. ‘Together, the volumes present nearly 2000 fabric designs, complete with their length, breadth, weight, place and price specifications, as well as detailed archival material on weaving patterns, techniques and processes, with a companion volume on natural dyes. The whole project reflects the British zeal for detailed study’. (Himal Southasian, May 2009).

During the last few decades, especially after the partition of India in 1947 and the creation of Bangladesh in 1971, there has been a growing interest in learning about the history of Bengal textiles and the use of traditional handloom-based production. In Bangladesh, for example, the government, soon after the birth of the country in 1971, set up a Jamdani cluster, in Rupganj, about 20 miles from Dhaka City. This place is situated in Dhemrai in Dhaka District in Bangladesh, one of the historically famous centres of textile production in Bengal. The place is also known as Jamdani Palli (Jamdani village) where the clustering process has brought together a large number of Jamdani weavers at one dedicated place. This allows interactions, cooperation, skills and experience sharing/learning and also where buyers can come to one place to order their Jamdani sarees. The clustering policy has already had some success in helping to develop a thriving community of Jamdani weavers producing traditional style handwoven cotton and cotton/silk mix sarees. They range from very simple to highly intricate and elaborately designed items. Today the village has about 450 units, each of which consists of living quarters and several looms. A family lives in one unit and the total number of looms per unit varies from two to four. This means that in total there are about 1000-1200 handlooms in this particular village. There are other centres of production of traditional textiles throughout Bangladesh and in West Bengal in India. Below are some images from the Rupganj Jamdani Palli.