First published on 7 July 2020

My first trip to Sydney, Australia, 2003

One of the boards at the Botanical Garden, providing a story of what happened to the Aboriginal people in Australia, 2003

The first time I remember learning something about Australia was in 1973 or 1974 during a special presentation at our school by an external guest who had recently returned to the UK from that country. It was at the Portway Junior School, in Plaistow in East London, my first school after coming to the UK in 1973. I arrived in London from Bangladesh in March of that year, and soon after the Easter Holiday I was enrolled at the school and placed in a third-year class under Mr Khalia, a teacher of Indian origin; this helped as, often, he explained things and gave instructions in Hindu/Urdu because my English was non-existence at the beginning. As Hindi/Urdu and Bengali belong to the north Indian family of languages, I could understand him a bit. I was at his class only for a few months as the school closed for the summer holiday in July of that year.

From September 1974, I was moved to the fourth and final year of Junior School education. By then, I had already picked up some English. It was some time during the fourth year at Portway Junior that our teacher announced that a special guest would be coming to the school to make a pictorial presentation on Australia. This excited everyone and I remember vividly how eagerly we all waited for the day, which was planned to be a joint session for all the fourth-year classes. The session consisted of a slide show on a screen and discussion by the guest. Looking at the images of Australia presented was quite wonderful, and the flora and fauna of the country looked very different from those in Bangladesh I knew and in London that I was getting to know. There were a couple of images of Aboriginal people also shown by the presenter.

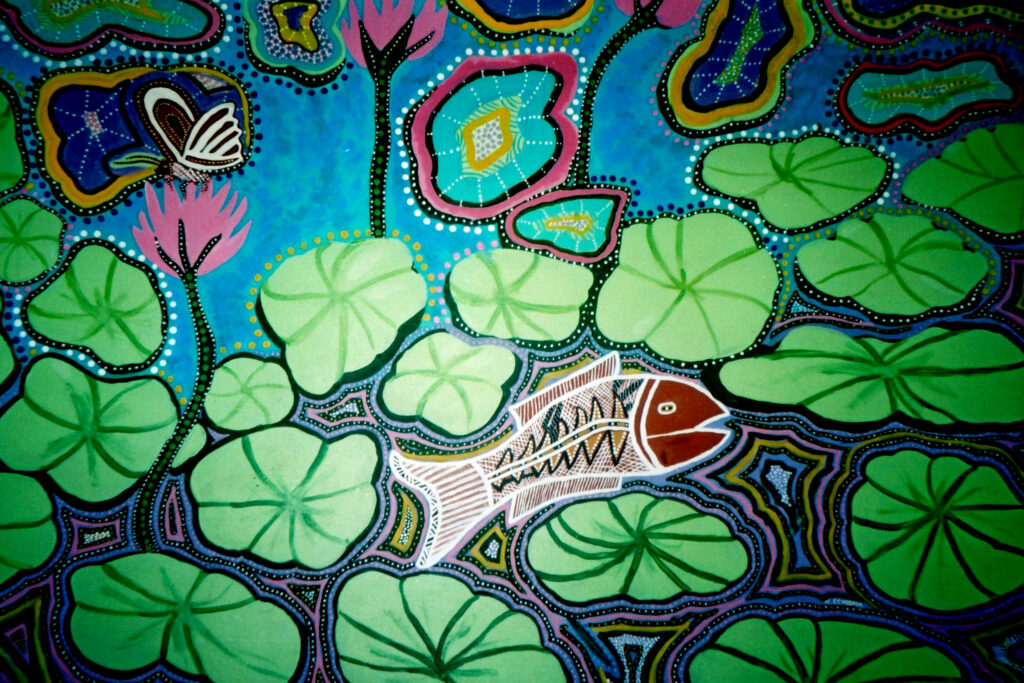

A picture of a painting at the Aboriginal Cultural & Education Centre: Muru Mittigar, 2003

As a child, images of Australia that I saw from the presentation fascinated me and everything about Australia looked very beautiful and different. Before that day, I knew nothing about Aboriginal people and the fact that the British went there by force, stole the continent and killed most of the original inhabitants. In fact, the British state renamed the settlers arriving as ‘Australians’ and called the continent Australia. During subsequent years, I learnt more about Australia and the indigenous Aboriginal people, although very little information on the continent or the people was available in London when I was growing up.

There used to be a weekly cooking programme on one of the British TV channels, where an Australian celebrity cooked and then invited someone from the audience to join him on the table as a finale of the programme. There were also occasional documentaries on Australia on British TV where sometimes they included limited footage of Aboriginal people. I distinctly remember seeing Aboriginal people in the documentaries in appalling conditions, although with beautiful white and coloured dots and paintings on their bodies and faces, where some were seen sitting on the floor and flies hovering around and touching their faces and bodies. Another source of information on Australia was a film that I saw based on a young boy’s relationship with a kangaroo and how a severe forest fire devastated their community. Later, when I joined the University of Essex in 1982, the film society’s schedule included, during one season, a film called Mengannini – about an Aboriginal woman who stole a young white child during a genocidal campaign by British soldiers in Tasmania, rampaging and massacring the Aboriginal people, where during the chase a relationship develops between the woman and the child. By then, I knew about the scale of the extermination of Aboriginal people in Australia and had recently learnt that in Tasmania the genocide was total where not a single individual from that unique ethnic group or nation of the island had survived the British extermination drive, so I invited many friends to come and see the film. Although the film was a bit disappointing as it did not cover much about the genocide and destruction of the unique population, I did develop some ideas of what had happened on the island.

It was during the 1970s, after arriving in London and learning about the fate of the Aboriginal people – as well as that of Native Americans and New Zealand Maoris – that I began to develop a deep sense of depression, sadness and anger at what the British did to these people. I desperately wanted to meet these people and developed a desire to do something to right the wrongs of the past, at least to some extent, so that a kind of redress for them can be achieved. In 1980, I was very lucky to meet a Native American from Canada, who came to London as part of a delegation to negotiate with the Queen of Britain on some treaty issues. He was standing amongst the crowd of the very popular speaker, Roy Sawh, in London Hyde Park’s Speakers Corner, looking distinct. I never saw face to face, before that day, any Native Americans, so I went up to him and asked where he was from. He replied Canada. I asked him whether he was a red Indian – even though his skin colour did not resemble any degree of redness that I am familiar with – his reply was an emphatic no and he pointed out that he was a native Canadian. I shook his hand, hugged him and nearly cried with emotion. I said I thought you were all dead. He said no brother we are still alive, and then he went on to tell me about the centuries of repression they faced and continue to face at the hands of the white man.

By 2003, when I first visited Australia, I knew more about the Aboriginal people – from reading, listening to presentations and through conversations with many people. One of my good friends, Satish Rai, who lived in the London Borough of Greenwich and served as a local Labour Councillor for many years had migrated to Sydney in Australia in the mid-1990s. We kept in touch. He was both a strong anti-racist campaigner in Greenwich and a very vocal, assertive and uncompromising individual when it came to racism and racial discrimination. We got to know each other while I was working for the local council and gradually became good friends.

I do not remember the exact month when I went to Australia, but it was perhaps in October or November 2003. I searched for my old passport from that period to check the exact dates but could not locate it. It was only for a short four days trip, which I decided to undertake very whimsically when I was visiting Singapore and several other South Asian countries. On a particular day or evening, during my travels, I suddenly developed an urge to go to the edge of the world – or ‘down-under’, often used as a synonym for Australia by the British and the settlers – to see and meet some surviving aboriginal people. So, I bought a Singapore Airline return ticket from Singapore to Sydney, contacted Satish and informed him about my visit. He invited me to stay in his house and offered to pick me up from the airport.

When I arrived early in the morning at Sydney airport, on my way out, I picked up some brochures about Sydney, one of which was a ‘what’s on’ publication that listed major coming days events and activities in the city. During the car ride to Satish’s home in Liverpool in Sydney, we discussed many things, including about life in London, how the people in London that we mutually knew were doing, what was Sydney like and its diversity, and where and how I could meet Aboriginal people.

The journey probably took about an hour from the airport and when we got to his house in Liverpool, I found it to be a very pleasant, comfortable, single-storey bungalow with a nice garden, situated in a quiet location. Satish, who is of an Indian origin, born and bred in Fiji, and his partner, Anju, also of a Fijian Indian origin Australian, welcomed me to their home, made me feel very comfortable and supported me in many ways to enjoy and get the best out of my trip to Australia.

With Satish in his house in Sydney, 2003

I also met one of my cousin sisters from Bangladesh who recently got married to a fellow Bangladeshi student and together they moved to Sydney to undertake higher education – both enrolled on separate PhD programmes. As well as Satish, my cousin wanted to do for me more than what I was able to receive.

As my main aim in visiting Australia was to meet Aboriginal people and see the city of Sydney – its city centre areas, suburbs, transportation networks, architecture, and so on – I first looked through the ‘what’s on’ brochure that I picked up at the airport to identify what I could and should do. In the publication, I identified one particular event that sounded very interesting was an aboriginal performance and presentation on their culture and music at either the Museum and Galleries of New South Wales or the Arts Gallery of New South Wales (I do not remember which one), situated within the Sydney Botanical Garden area. I also found information on the Aboriginal Cultural & Education Centre called Muru Mittigar. My friend Satish and his partner told me that I should also go to a station called Redfern, where I would be able to see and meet Aboriginal people as this was the main location for the community in Sydney.

I did not keep a diary during my trip so I am writing this from my memory. This means that aspects of the chronological order of my Australia trip are no longer clear in my mind, although everything that I write about in this piece took place during four days of my stay in the country. Satish suggested that we meet later at his office in Liverpool after I finished visiting Redfern.

I had imagined Redfern to be an area where I would see cafes and shops run by Aboriginal people and that there would be many members of the community on the streets engaged in a variety of activities. When I got to Redfern Station and while walking out the first thing I saw did not displease me but it actually reinforced my expectation. What I saw was a brick wall standing in front on the other side of the road from the station’s entrance. What did I see on the wall? I saw a set of Aboriginal paintings, and behind the wall high structures of the modern city was strongly represented.

A scene from the front of Redfern Station, 2003

In contrast to the heightened expectation, soon my hope of seeing and meeting Aboriginal people started to become dashed as I saw none on any of the streets in Redfern that I entered and walked through. I thought, maybe, there are small places of concentration, so I kept on walking around for several hours but saw none. However, I did see all kinds of other people – Chinese, Vietnamese, Indians, Europeans, Pacific Ocean islanders, Middle Eastern, and so on – but no Aboriginal people.

After getting tired, I went to a Macdonald’s restaurant for rest, bought a cup of coffee for some caffeine and pondered about the situation and the issue. I thought how comes even though I came to a place that is supposed to have a large concentration of Aboriginal people in Sydney I could not see a single individual from that community. This made me feel very sad and disappointed, and I took the train back to Liverpool and walked to Satish’s office. I told him about my experience of visiting Redfern and my disappointment of not seeing a single individual from the Aboriginal community. One of his female colleagues, an Indian Australian, joined us and wanted to hear about my trip to Australia. On being told of my disappointment in Redfern, she immediately asked me why I wanted to go there and told me that I should not want to meet these people. She also added that the Aboriginal people were lazy and suggested that the reason why I did not see any of them there was because they were most probably sleeping during the day as they were drunk last night. I was shocked, disappointed and felt sad at the reaction of this lady, but without escalating the issue and having a fight I decided to focus on how I might be able to meet Aboriginal people.

During the early evening and on the next day, I spent most of my time looking around and enjoying the city, eating halal food from Lebanese restaurants, walking around and travelling in Sydney’s highly developed and efficient transport network. I found Sydney to be a very beautiful city, cleaner and greener than London and most people were very friendly and helpful. The city centre had full of places for buzz and to eat, shop and be entertained. It was incredibly diverse in terms of population and cultures and included ethnicities and people with physical and facial characteristics and features that I never saw in London or anywhere in the UK. I imagined that, perhaps, some of them were Pacific Ocean islanders – a few individuals that I encountered were real giants. On several occasions, I nearly thought that I was in Singapore or Hong Kong as Chinese looking people had an overwhelming presence in certain areas resembling many Asian cities in terms of population, shops, restaurants and businesses.

I used the route through the Botanical Garden to join the Aboriginal show at the Museum or the Arts Gallery to enjoy some Australian greenery before arriving at the venue. In the garden, I took pictures of around twenty longboards along one of the paths, on the ground, presenting a story of the Aboriginal people.

One of the boards at the Botanical Garden, presenting a story of what happened to the Aboriginal people in Australia, 2003

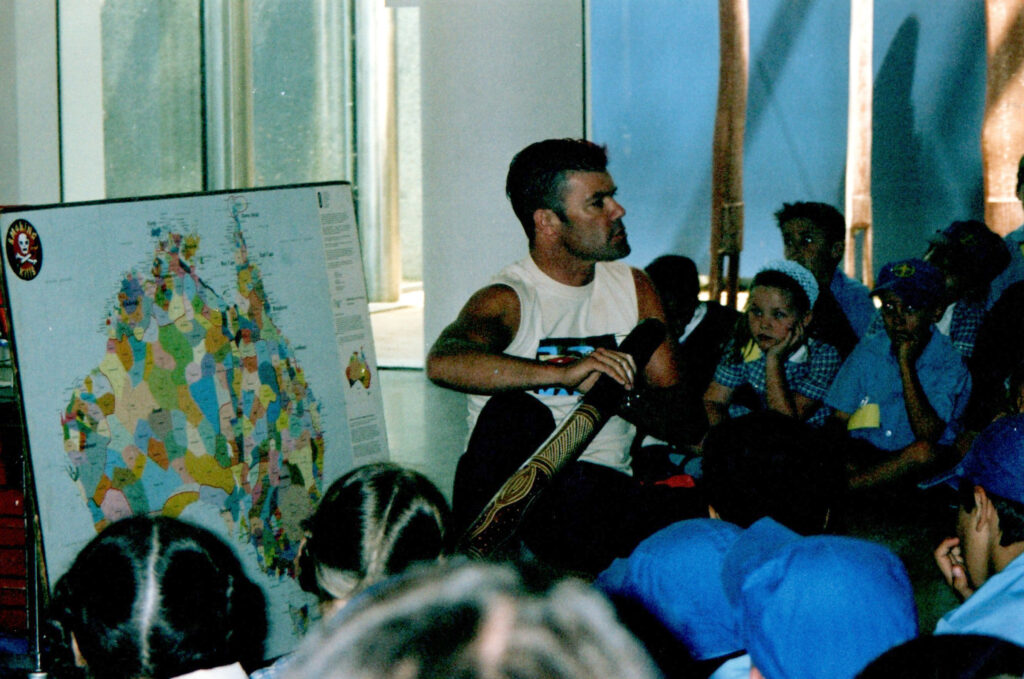

When I arrived at the venue, looking at several exhibits following the direction to the location of the event, within the gallery or museum, I saw a few people entering and taking their seats and some individuals in the performing area making preparations, placing and arranging didgeridoos and other items. All these people were white. I imagined that at any moment a group of Aboriginal performers would arrive and could not wait for the moment. However, to my dismay, no aboriginal people arrived, and the show started without them, that is what I thought. By then, groups of school children had arrived and sat in a semi-circular fashion near the performance area and the large room became filled with visitors sitting or standing at the back.

My dismay was partly due to my ignorance about Australia and its people, particularly around racial mixing concerning Aboriginal and white people. It was also partly due to the mass genocide, racism and destruction by the British and their settlers in Australia. On the racial question, the presenter/performer introduced himself as an Aboriginal, although, to me, he looked completely white. He said that where he comes from his father is known as a ‘black fella’, his mother a ‘white fella’ and he a ‘yellow fella’, and then proceeded to interactively engage with the audience, particularly the school children, with his instruments and stories. Although to an extent I enjoyed attending the event, I could not accept the fact that a white man was claiming to be an aboriginal and making the performance/presentation on Aboriginal culture. Later, I learnt more about racial mixing in Australia from mixed-race Aboriginal/white people that I met and conversed with.

Performance/presentation at Museum and Galleries of New South Wales or at the Arts Gallery of New South Wales

One thing that I noticed very clearly was the absence of people of African origin in Sydney. I saw none – not a single soul – which surprised me a lot as in London, Europe and America, people of African origin are inseparable parts of the very fabrics of society – their presence and contributions are deep and extensive and seen and felt everywhere. I asked myself, how could this be? It does not mean there were none, but the fact that I did not see any during my short trip, it means that the number of African origin people, who might be living in Sydney in 2003 must have been minuscule.

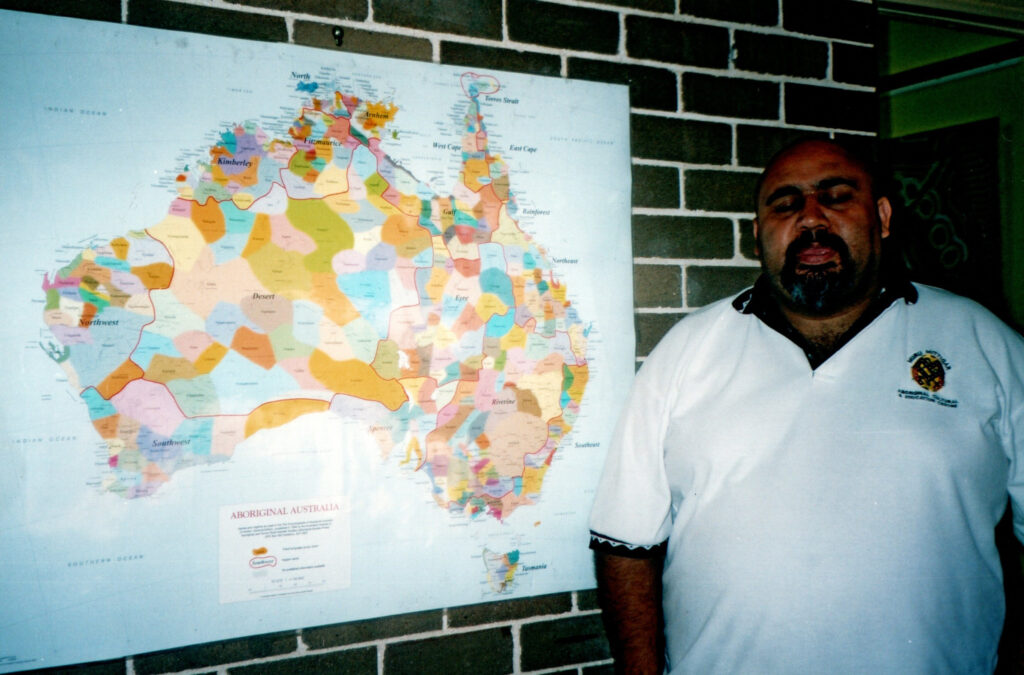

A day later in the morning, I called the Muru Mittigar centre by phone, which was answered by a man called Roy. I explained that I wanted to come and visit the centre to meet Aboriginal people to learn more about their cultures and history and asked whether anyone would be available to talk to me. He said yes and that he would be very happy to meet me, but pointed out that he would be there only until about four or five pm. He gave me direction and said that the centre was near the Blue Mountains. When I got there, perhaps around 3 pm, the lady at the reception asked me to wait as Roy was on the telephone.

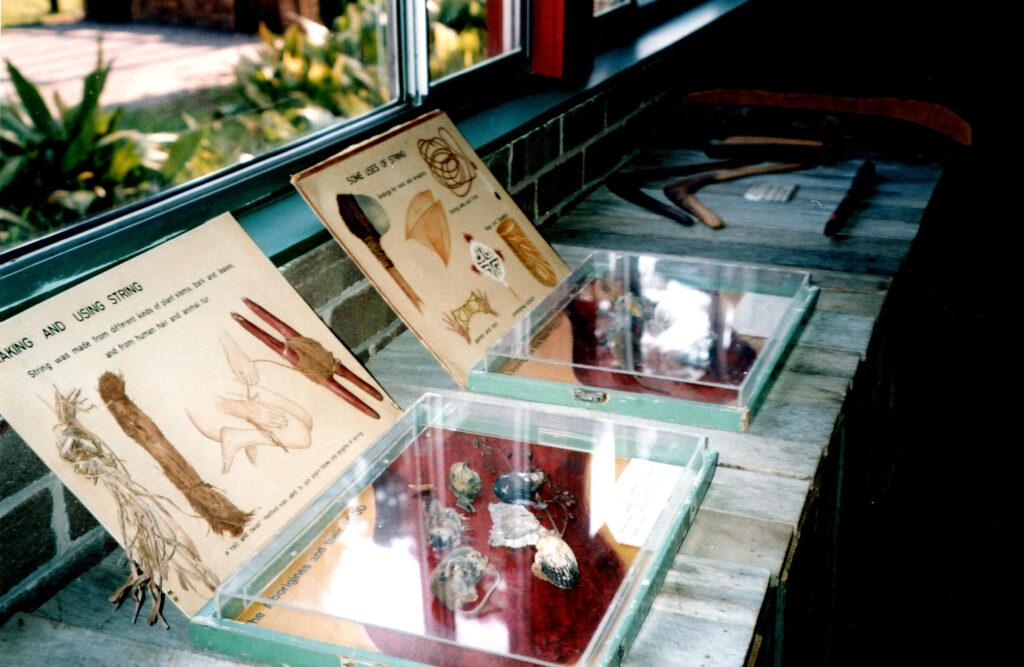

While waiting, I looked around and saw Aboriginal paintings; exhibition boards depicting their history and traditions; boomerangs, tools and didgeridoos. We had a short conversation. Although she looked white with a slight Mediterranean tan, she informed me that she was an Aboriginal woman, the product of her Aboriginal grandmother being raped by a white man. She was extremely bitter about that and about the racism and violence they faced and continue to face in Australia. It seemed that she had a strong determination never to forget her Aboriginal roots and what was done to her people in Australia.

When Roy came out of his room to welcome me, I was surprised as he did not look Aboriginal at all, or at least not what I imagined to be the range of Aboriginal looks. To me, he looked more like Indian. He took me to his room, made me a cup of tea and then we began to have a conversation, which lasted longer than planned. From him, I learnt more about Australia, Aboriginal people, racial discrimination, identity issues faced by Aboriginal children and so on, including about his family – his father was Aboriginal, mother white and he had five other siblings. One of the most memorable things I remember from the discussion was that when he shared an interesting experience with me, which I could relate to from my personal experience in London. It was during an Aboriginal barbecue, he said, he overheard a discussion between some Aboriginal children, when one of them claimed that he was not an Aboriginal but an Indian. So, he went to the young boy, held and twisted his ears and asked him what he had said. The young boy apologised, who was then told never to do that again and encouraged to learn to feel proud of their Aboriginal identity. During our conversation, I explained to Roy that they were never going to get their country back, so the best option for the Aboriginal people in Australia was to focus on developing their communities and making progress within modern Australia – by educating themselves, increasing their population, engaging economically, making external friends with people from outside Australia and exploiting their beautiful cultural potentials.

Roy

Our mutual level of interest in the discussion resulted in Roy staying more than an hour longer in the centre than he originally planned. When it was time to go, he insisted on driving me back to the Sydney city centre as he was going in that direction, which I accepted gladly as it provided further opportunities and time to discuss more things during the journey back to the centre. When he dropped me, I thanked him and said see you next time. He also said the same thing and gave me his business card.

On the next day, while Satish was driving me back to the airport, I continued to express my disappointment at not seeing any full-blooded Aboriginal people in the biggest city of the continent that belonged to them for tens of thousands of years. I also reflected on this, empathised with the experiences of mixed-race people that I met and heard about, and wished them good luck. But in my mind, I could never accept this fact, which I found very sad, disgraceful and heart-breaking. Perhaps, there are some full-blooded Aboriginal people in Sydney, but the fact that I did not see any, this means that something was very seriously wrong with Australia.

A picture of a painting at the Aboriginal Cultural & Education Centre: Muru Mittigar, 2003

An inspiring article and very apt in this era of Black Lives Matter. The lack of presence of the indigenous people in Sydney was a long calculated ploy by the settlers. In one stroke Australia was deemed to be terra nullius, a no man’s land, as the Aboriginees were adjudged not to have any culture of owning properties! This gave the settlers the licence to embark on their pogrom. But you would find people in Sydney and across Australia today pouring scorn on BLM movement and saying All Lives Matter, without seeing how uncharitable and evil it sounds to utter it.