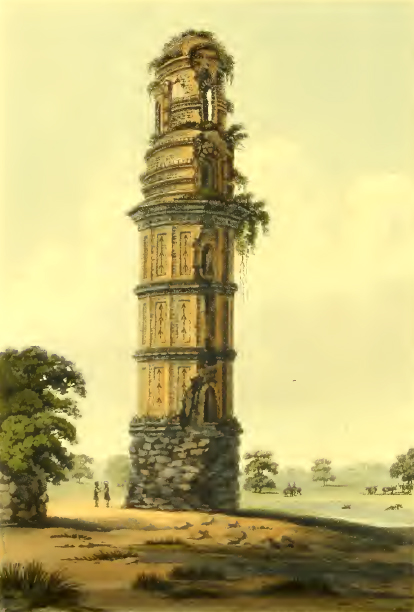

1487-94

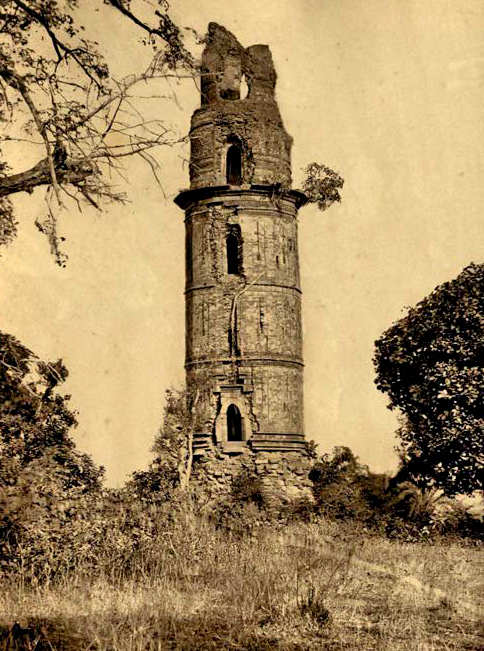

(Firuz Minar is attributed to Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah, the second Habshi ruler of Bengal,

image from ‘Gaur: Its Ruins and Inscriptions’ – by John Henry Ravenshaw, 1878)

Background

A few years ago, a Somali artist in East London, Kinsi Abdulleh, reminded me that black history was more than just slavery. The reminder happened when we talked about Black History Month while coming out of some events at the Rich Mix Centre. I wanted to discuss slavery during our conversation for two reasons. First, slavery and the enslavement of Africans to the Americas have been a subject of research and debate in Black History Month programmes since its inception. Second, which was my main reason because I thought I had discovered a possible link between Bengal textiles and trans-Atlantic slavery, which she would find interesting and that it would be a relevant topic for discussion at future Black History Month programmes. But before I could elaborate, she interrupted and said that she was fed up talking about slavery all the time and suggested that we should explore more positive aspects of black people in history.

During 2011-2013, I delivered a project in East London called ‘How Villages and Towns in Bengal Dressed London Ladies in the 17th, 18th and Early 19th centuries’, which included researching the history of Bengal textiles. When I examined East India Company imports and export figures from records at the British Library, I found data that, during the late 17th Century and most of the 18th Century, Bengal textiles grew to dominate East India Company imports from the whole of Asia. Other locations from where the East India Company imported textiles from the Indian subcontinent into Britain were Gujarat, Bombay and Madras. However, the quantity from these places decreased over time, whereas the total from Bengal increased.

Most sources I consulted on the links between Indian textiles and trans-Atlantic slavery referred to Gujarati textiles. This was due to the high demand for Indian textiles in West Africa, which acted as a form of currency when purchasing enslaved Africans by the British. However, when I studied the data carefully, including the re-exports to West Africa of imported textiles by the East India Company from India, I found that there was still a gap that only an element of Bengal textiles could fill. This point was which prompted me to mention slavery during our short conversation.

But she was assertive and insistent that we should break with the past and stop viewing slavery as the only or main experience of black people in history. Then, she asked me, “Do you know that there were once great African rulers of Bengal?” I replied yes and said that I didn’t know much about it. She suggested I look into that and explore more of the positive historical links between Africa and Bengal.

At the time of our conversation, my knowledge of the subject was quite limited, and what I did know was from reading some limited materials more than twenty years previously. Although I could not say much about the topic, the rule was only for about four or five years; therefore, it was not very significant in the history of Bengal.

However, I have now realised that my earlier judgment concerning the importance of the period of African rule of Bengal was not quite right. I began to ask myself how there could have been a period of African kings in Bengal when there was no African invasion of the country, or the size of the African community was sufficiently large at any time to enable this to happen. As the African rule of Bengal did happen, given the context during the late 15th Century, it was indeed something significant that needed to be understood and explained. When I started to investigate the subject, to my surprise and disappointment, I could not find any serious attempts by scholars to understand the ‘Habshi rule of Bengal properly’.

During 1487-94, the Bengal Sultanate was ruled by a series of kings of African origin. From the beginning of the Muslim rule in northern India, in addition to Turkish slaves, enslaved Africans were brought to India to serve nobles, military commanders and the sultans, primarily as slave soldiers. Some rose through the ranks and achieved high positions by becoming military commanders, senior officials, nobles, governors and even rulers. In the case of the Bengal Sultanate, several Africans became the rulers, but this was only for a very brief period. It is most likely that not all enslaved Africans brought to India were strictly from Ethiopia. They most probably were from complex African origins and mixes with a majority from Ethiopia and collectively called Habshis by the Muslims or Abyssinians by European Christians. In this paper, the terms Habshi (Habshis), Ethiopia (Ethiopians) and Abyssinian (Abyssinians) are interchangeable.

Preparation

I recently (October 2020) developed a renewed interest in the ‘Habshi rule of Bengal’ and delved into it with hardly any background on the topic. As such, I tried to gather as much valuable and relevant information as possible within a tight deadline that I set for myself – 31 December 2020. I first sifted through the materials I collected – the sources, records and interpretations – and then focused on those that seemed to be the most relevant. Naturally, Google search was the first step in seeing what was out there on the topic. Wikipedia entries emerged at the top of my computer screen, and, as usual, they included both reliable and unreliable information. The Internet searches brought out relevant Indian newspaper articles, blog posts and references to books and articles.

Over a very short period, I acquired many relevant historical materials and scholarly interpretations of various aspects and background contexts of the Habshi rule of Bengal. They included a few recent works that sought to correct past mistakes based on either reinterpretation of earlier sources or examination of freshly discovered materials, such as new coins and inscriptions. Going through them, I realised more properly that this period of Bengal’s history, though significant, was not adequately understood except in a very generalised and brief fashion. There seems to have been very little interest among scholars to try to understand and explain how it was possible, within the context of the period, for there to be a period of ‘Habshi rule of Bengal’ and why it only lasted just over six years (1487-1494).

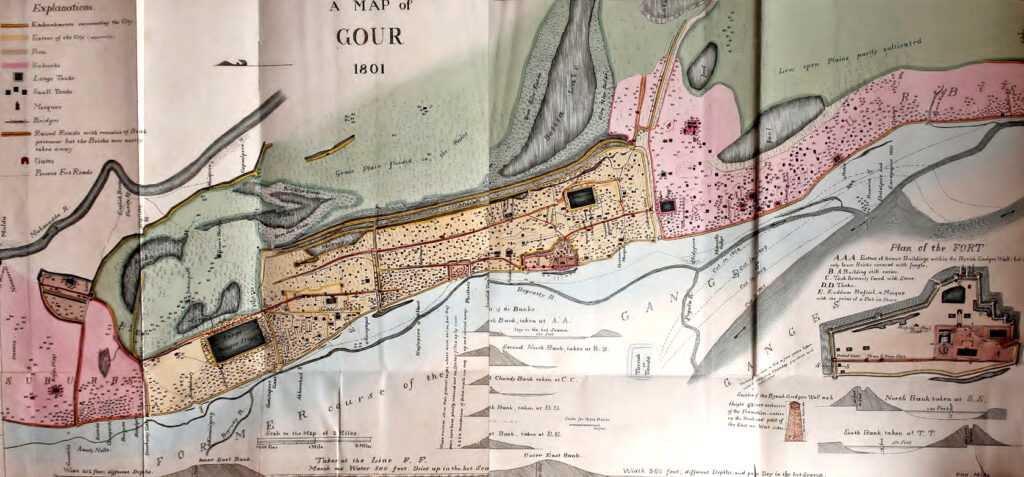

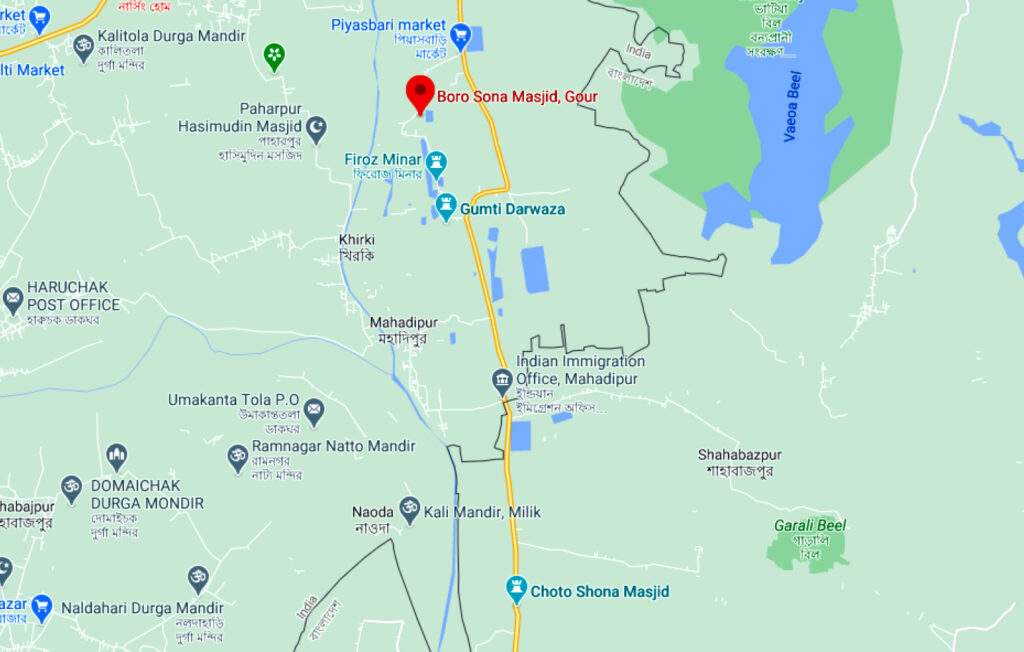

The city of Gaur – whose other name was Lakhnauti – was the capital of the Bengal Sultanate at that time, a large city by the standards of the period. The Italian Ludovico Di Verthama, who visited Gaur during the first decade of the Sixteenth Century, described the capital Bengal as the ‘the best place in the world, that is, for living in’.

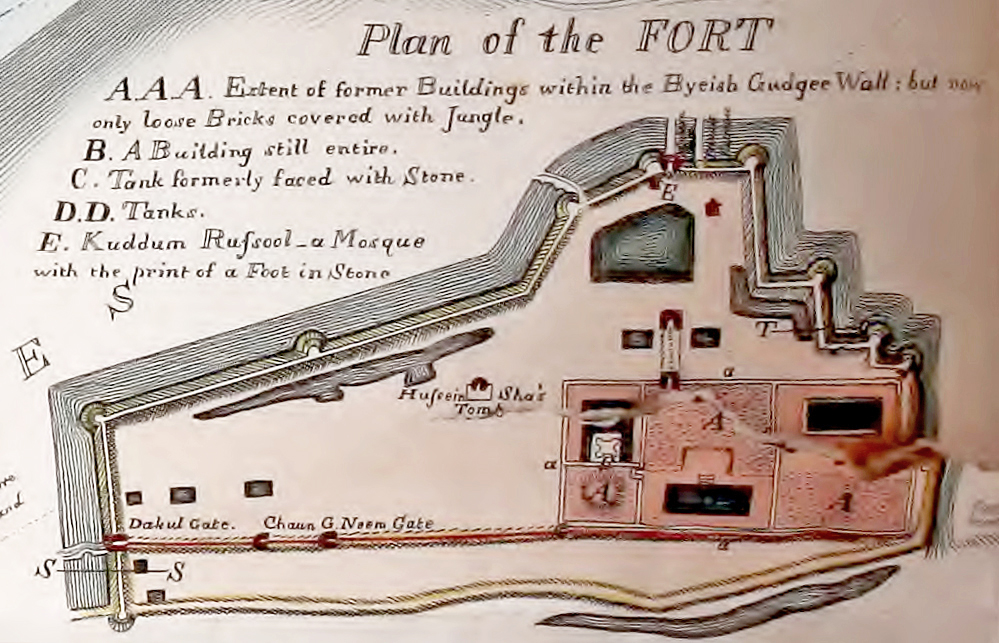

A small part of that city now lies within the border of present-day Bangladesh in Chapai Nawabganj, the rest being in the northwest of the border in Malda in West Bengal, India. According to Henry Creighton, based on his surveys, visits and drawings on the ruins of Gaur, carried out during the early years of the 19th Century, the city stretched with a ‘continued population, for nineteen miles long, by a mile and a half wide’.

(Ruins of Gaur – by Henry Creighton, 1817)

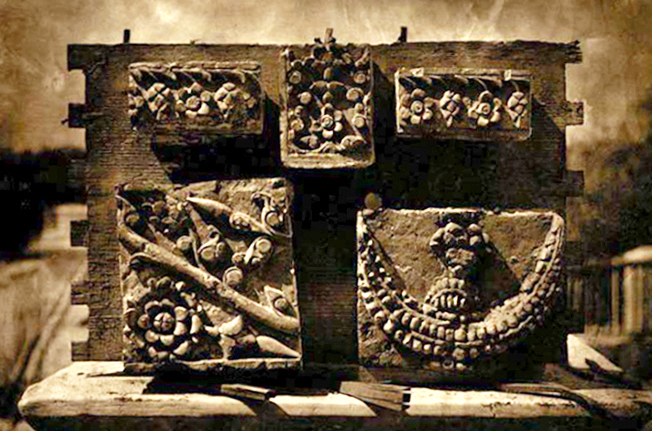

That time, Gaur must have looked relatively new and quite beautiful. The capital reverted from Pandua, according to some, during the reign of Sultan Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah (1415-1433), the son of Raja Ganesh, who converted to Islam. Others hold that, based on analyses of new coins, the move took place during Sultan Nasiruddin Mahmud Shah (1433-59). Regardless, the capital was previously moved from Gaur to Pandua at the beginning of the 1340s, just before the Ilyas Shahi dynasty was established. Many of the buildings and other facilities in Gaur that existed during the ‘Habshi rule of Bengal’ were constructed after it had reverted to its capital status, including the royal palace, during the rule of the first two restored Ilyas Shahi sultans: Sultan Nasiruddin Mahmud Shah (1433-59) and his son Sultan Rukunuddin Barkbak Shah (1459-74). However, most of the buildings of the period no longer stand, including what must have been the beautiful Gaur Royal Palace. Only a few religious buildings have survived, some in relatively good condition and others in ruins.

(Ruins of Gaur (paintings by Henry Creighton, 1817; photographs by John Henry Ravenshaw, 1878)

Most of the writings on the ‘Habshi rule of Bengal’ (1487-94) that I have seen are very generalized and brief. They narrate the story of how a Habshi eunuch called Khawajesara, who called himself Sultan Shahzeda Barbak Shah, after killing the last Ilyas Shahi ruler, Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah, in 1487, usurped power to become a very short-lived sultan. Because within a matter of a few months, he was said to have been killed and deposed by Malik Andil, the loyal Habshi commander of Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah, who became the new ruler in the same year and called himself Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah.

Most narratives state that Malik Andil was reluctant to take over power after he had killed Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah. For him, his action to depose the usurping eunuch Sultan was only to avenge the killing of his master, Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah, and restore the throne to its rightful owner, the young son of the murdered sultan. However, the dowager queen, the wife of the murdered Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah, did not want her son, being just two years old, to become the new sultan and the Sultanate ruled by a regent until the infant sultan reached maturity. Instead, she requested Malik Andil to take the position as she had promised God that she would make whoever killed the usurper, Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah, the new sultan. The nobles supported the dowager queen’s position as Malik Andil had a good reputation and was regarded highly by most at the court.

Malik Andil became the new sultan in 1487 and called himself Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah. Although the nature of the nobles at court and their compositions have not been discussed anywhere, based on the understanding that I have developed so far, it is highly likely that many individuals with an Abyssinian origin were a significant part of the Gaur nobility of the time and enjoyed powerful positions of influence in the military, politics and society.

The rule of Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah lasted for just over two years, and there exist controversies regarding how his life ended in 1490 – whether he died from natural causes or a rival killed him. Regardless, historians have painted him positively as a good and just king who brought stability to the country – even though some of his contemporaries were worried that he would bankrupt the treasury through his public works programme and excessive concern for those in need in society.

After Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah died or was killed in 1490, a young child named Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah was enthroned. This new sultan did not enjoy the position for long as he was killed and deposed within a year of his enthronement by another Habshi named Sidi Badr Diwana, who then established himself on the throne as Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah in 1490. Sidi Badr Diwana first murdered Habash Khan, the prime minister, who was the regent protector of Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah. He then killed the young sultan and installed himself as the new sultan, Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah.

In contrast to the rule of Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah, who was considered a wise and benevolent ruler, Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah has been depicted as the opposite. He was said to have been unwise and cruel, who eliminated potential rivals, increased taxation and foolishly reduced the pay of the army. It has been argued that these actions led his Prime Minister, Hussain Sharif, to switch sides and work with dissatisfied nobles and rivals at the court and outside to organise a rebellion. The rebels successfully killed Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah in 1494, which ended the brief ‘Habshi rule of Bengal’. After that, the Hussain Shahi dynasty was established by Hussain Sharif. The new dynasty ruled the Sultanate for several generations until 1538 when it ended with the victory of the Afghan Sher Shah over the last Hussain Shahi ruler, Ghyasuddin Mahmud Shah.

Sources of information

Historians and researchers usually have access to four types of sources to construct the history of the ‘Habshi Rule of Bengal’. There exist disputes about the exact time period of each of the Habshi sultan’s rule, although some recent discoveries and studies have made the situation clearer and more accurate.

The first sources consist of two books. One called Tarikh-i Firishta, written by Muhammad Qasim Hindu Shah (Ferishta) during the first decade of the 17th Century, more than one hundred years after the Habshi rule had ended and the second, called Ryiazuddin-s-Salatin (A History of Bengal), written by Ghulam Husain Salim, in around 1778, nearly three hundred years after the episode.

The second sources are coins and inscriptions from the period. They provide useful information and help correct and confirm dates, names and details of past events, such as mint towns or the territories under the control of the rulers. Although they are more reliable, the information they provide is very limited.

The third sources are accounts of several European visitors or chroniclers some of whom wrote without ever setting foot in Bengal: an Italian who visited the city of Gaur in 1505 and two Portuguese officials who wrote on Bengal during the 1510s without ever experiencing the soil of Bengal, such as Tom Pires.

An Italian visitor Ludovico Di Varthema who visited Bengal in 1505, provides the earliest written piece on that part of the world after the disappearance of the ‘Habshi rule of Bengal’. He gives some details of the Sultanate state, its power structure and military strengths, the economy and the population, for example, but he is silent on the Habshi rule. Another piece of writing in this genre was an account by the Portuguese official Duarte Barbosa, who provided some details and descriptions of Bengal and the capital city of Gaur during the first decade of the 16th Century but did not include anything on the Habshi rule or anything about the Habshis in Bengal.

Tom Pires, in contrast, wrote about the Abyssinians in Bengal. He also made some strange and contradictory remarks about the people of the land. Tom Pires described how the Abyssinians exercised powerful influences within the Bengal Sultanate and listed some examples. However, he did not write anything about any recent rule of the Abyssinians in Bengal.

He wrote about Bengal without visiting the place around 1512 while in Melaka, present-day Malaysia. His accounts state that the Abyssinians were in powerful positions in Bengal during that time, which contradicts Ghulam Husain Salim, who in the Riyaz claimed that the Habshis, in their entirety, were deported out of Bengal soon after the establishment of the Hussain Shahi Dynasty in 1494.

The fourth source is materials gathered and generated by British officials, which started several decades after the British takeover of Bengal in 1757. They collected, preserved and interpreted materials they found, discovered and received as gifts – including coins, inscriptions and manuscripts. They also created drawings of decaying walls, gates and buildings; carried out scientific surveys of the ruins of Gaur as they existed when they visited; identified and mapped the ancient city and its constituent parts.

These provide useful contextual information in developing and constructing an evidence-based account of the rules and dynasties of the Bengal Sultanate. The ‘Ruins of Gour’ by Henry Creighton (1817) and ‘Contributions to the Geography and History of Bengal: Muhammedan Period’ by Heinrich Blochmann (compiled by The Asiatic Society in Calcutta in 1968 from Blochmann’s published essays in the Journals of the Asiatic Society in 1873, 1874 and 1875) are valuable works that are studied by historians interested in understanding the Habshi rule and the wider Sultanate period.

They, however, provide very little contextual information on the ‘Habshi rule of Bengal’. Without an understanding of the contexts, it becomes difficult to know how and why things happened. The task of making good judgements becomes infinitely more difficult, especially not knowing about the personalities involved and their qualities, the shifting power politics, transitions from one sultan to another, the nature of internal and external threats, etc.

The Ilyas Shahis

The year 1487 was when it ended, what historians have defined as the Ilyas Shahi rule of the Independent Bengal Sultanate. It began during the 1340s when Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah defeated the Delhi Sultanate-appointed governors of Lakhnauti and Satgoan and occupied only some parts of Bengal. However, his control expanded and consolidated during the 1350s to cover all three Bengal regions, including Sonargaon, that the Delhi Sultanate previously ruled through governors. As such, the Ilyas Shahis ruled for nearly one hundred and thirty years with a short period of interruption by what became known as the usurpation of Raja Ganesh, a Hindu minister, and the subsequent enthronement of his son, Sultan Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah, who converted to Islam, and for a very brief time, also the latter’s son, Sultan Shamsuddin Ahmed Shah. This phase took place between 1414 and 1434, a total of twenty years, and, after a short power struggle, a new ruler was established, who called himself Sultan Nasiruddin Abu Muzaffar Mahmud Shah.

The chaotic period of the last days of the ‘interrupted period’ focused the minds of the nobles in the capital who considered how to re-establish a stable rule in Bengal. It led them to look for a suitable descendant of the Ilyas Shashi dynasty, who they soon found. His name was Mahmud, and he was said to have been living, at that time, as an agriculturalist. Mahmud’s enthronement has been described as the restoration of the Ilyas Shahi rule, re-established after being interrupted by the ‘usurpation’ of Raja Ganesh and his son, who converted to Islam, and his grandson. From the restoration in 1434 until 1487, when it was permanently ended by the short Habshi rule, a total of five Ilyas Shahi sultans ruled the Sultanate of Bengal.

Looking at the Ilyas Shahi sultans, who they were and what they did during their rule may help reveal some interesting insights into why there was a Habshi period after their demise. The end of the Ilyas Shahi dynasty can be partly explained by the Habshi eunuch’s murder of Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah in 1487, the last Ilyas Shahi ruler. However, it cannot explain everything, especially why the dynasty could not come back, after the ending of the Habshi rule. It was permanently ended in 1487 and couldn’t return when the Habshi rule was ended in 1494.

Two factors are crucially important in this regard and would have undoubtedly contributed to how things unfolded during the restored Ilyas Shahi rule. First, according to Ferishta, during the rule of Sultan Rukunuddin Barbak Shah (1459-74), about eight thousand Abyssinians were brought to Bengal to serve mainly as soldiers. Second, among the five sultans who ruled during the later Ilyas Shahi period, the first was the father of three sultans and grandfather of one.

Sultan Nasiruddin Mahmud Shah was succeeded by his son, Sultan Rukunuddin Barbak Shah, who was succeeded by his son, Sultan Shamsuddin Yusuf Shah (1475-81). However, from then on, things went in a bizarre succession direction. The next ruler who ascended the throne was Sultan Nuruddin Sikandar Shah (1481). Surprisingly, he was not Sultan Shamsuddin Yusuf’s son but his father’s brother, an uncle. However, due to’ lunacy’ and possible incompetence of Sultan Nuruddin Sikandar Shah, he was soon replaced by one of his brothers, Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah. This means that after the reign of Sultan Rukunuddin Barbak Shah’s son, Sultan Shamsuddin Yusuf, the dynasty did not continue down the line through the sons of rulers but went back up and continued horizontally from that point until the demise of the dynasty in 1487.

After the rule of Sultan Nasiruddin Mahmud Shah, from 1435 to 1459, three of his sons and one of his grandsons ruled. This indicates that there was a crisis that prevented a normal progeny-based succession. There is no indication from historical reports as to why his son did not succeed Sultan Shamsuddin Yusuf Shah, how it was that his uncle came to the throne and why, and after the removal of that uncle, why another uncle became the sultan. As the historical accounts do not provide the ages of these people, it is difficult to speculate on possible age-related factors that could have caused the succession troubles. However, there must have been some age-related factors, or Sultan Shamsuddin Yusuf Shah did not have a son, or possible family feuds or other factors might have caused the early deaths of potential young sultans.

In any case, instability likely began to infest the Sultanate by the late 1470s, especially after the long fifteen-year reign of Sultan Rukunuddin Barbak Shah. When Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah was killed in 1487 by the Abyssinian eunuch, who became known as Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah, the late sultan only had an infant son, and there are no mentions of whether he had any daughters.

This could be one of the reasons why the Abyssinian eunuch moved against the sultan, as there were no obvious or potential Ilyas Shahi successors around. One reason that has been cited why the Abyssinian eunuch moved to kill Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah was that the sultan was trying to curve the growing power of the Abyssinians in the Sultanate and reign in their expanding influence in Bengal – thus triggering a pre-emptive action on the part of the Abyssinian eunuch. The fact that it was not the descendants of the Ilyas Shah rulers who retook control of the Bengal Sultanate after the Abyssinians were removed from power within less than seven years shows the weakness of the Ilyas Shahi descendants in Bengal at that time. It may partly explain why and how the ‘Habshi rule of Bengal’ got started. The potential of the Ilyas Shahi bloodline had finally run out of steam, and the Abyssinian rule only helped speed up the process of their demise.

Although Ferishta states that during the reign of Sultan Rukunuddin Barbak Shah, many Abyssinians were brought to Bengal, there is no information about how they came – whether by sea from Gujarat or the Deccan or by road and river from Delhi and elsewhere. Given the context, they were more likely brought in by ships from western India. Also, historical documents on the period, whether by Ferishta, the Riyaz or any other, do not say whether they were brought during a short period, all at once, or in small numbers over the fifteen years rule of the sultan and whether they continued to come after the death of Sultan Rukunuddin Barbak Shah in 1474.

Breakdown details of the Abyssinians brought to Bengal – how many eunuchs, soldiers and those appointed to a range of other positions – are not mentioned in historical records. How many were slaves and how many were freed ex-slaves are also not mentioned. Based on my knowledge of Islamic interpretations of politics at that time, someone who was a slave – owned by someone else – could not become a ruler. This was due to the condition of being a slave – as a slave has a master, he cannot exercise the powers of the sultan independently. This is because if someone is owned by someone else, then theoretically, he must follow and obey the orders and wishes of his master. This means there must have been some Abyssinian ex-slaves in Bengal who achieved manumission – officially became freed ex-slaves – by the time eunuch Shahzada took over as the sultan of Bengal in 1487.

How the Abyssinian rule began

Before discussing the rule of each of the four Abyssinian sultans of Bengal, it is necessary to make one important thing clear at this stage. The nearly seven years of ‘Habshi rule of Bengal’ cannot be described as a Habshi dynasty, as none of the Abyssinian sultans who became rulers in quick succession managed to establish any dynasty. The nearest thing to a dynasty that was conceived during the reign of Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah and implemented shortly after his death was the appointment of his incredibly young son to the throne, who was the third Habshi ruler called Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah. There is, however, a dispute about who was this sultan. Until recently, it was held by some that he was the son of Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah, the last Ilyas Shahi sultan of Bengal, who was murdered and replaced by Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah, the Abyssinian eunuch. Based on reading various accounts, including new studies of coins, it seems that Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah was indeed the son of Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah.

Another reason for this conclusion is that by the time Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah died or was killed in 1490, the son of Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah would have been around five years old. Although there has been child enthronement before and after around the world, where an elected or appointed regent ran the government’s affairs, this is unlikely to have taken place in this case as interpretations of some coins minted during his rule have shown that he was called the son of Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah.

A problem that prevents a conclusive outcome in this regard is that Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah’s son, Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah, who became the new sultan, was also young, although no sources mention his age at the time of ascending the throne. Some have suggested that Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah was the son of the murdered Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah but was adopted by Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah, the loyal commander of Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah. This story may be accurate but is unlikely based on the interpretations of details and dates on coins minted under Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah’s reign.

The ruler of Bengal immediately before the start of the Habshi period in 1487 was Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah. He ascended the throne in 1481, following the removal of his brother, Sultan Nuruddin Sikandar Shah, from power after reigning for a very brief period, ranging from one day to six months.

According to Ferishta, after his enthronement, Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah succeeded in raising the ‘court of Bengal to a more respectful footing than it had hitherto been’. He was also said to have enlisted a regiment of paiks, usually described as foot soldiers, some of whom would have been Hindus, to act as his palace guards.

A tradition of daily rituals developed where the paiks would march around the palace every morning until the king’s appearance, after which they would be relieved. Ferishta claims that one day, ‘one of the eunuchs of the palace, having gained over the guard, murdered the king’. After that, the eunuch established himself as the ruler of the Bengal Sultanate, calling himself Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah. But Ferishta provides no information about how that was done – the particular eunuch ‘having gained over the guard’ – and whether the murder was pre-planned and who else was involved in support of the eunuch. Was the murder born of a reaction to some prior incidences or the result of a heat-of-the-moment situation? No answers to these questions are found in any of the sources.

The next step that the eunuch sultan took, as stated by Firishta, was consolidating his power. He was said to have ‘collected together all the eunuchs of the palace, as also men of low station and desperate fortunes’, who were interested in improving their situation, to help strengthen his hold on to power. However, the ‘chief officers and nobles of the state… resolved together to depose’ the eunuch. What is interesting here is that not all the eunuchs at the palace would have been from a Habshi background, and similar would have been the case for the ‘men of low station and desperate fortunes’ who were ‘collected together’.

For Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah to move against Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah, who had restored Bengal to ‘a more respectful footing,’ it could not have been possible without a prior conspiracy and support from a significant section of the nobles and officers at the court who were perhaps also dissatisfied with the sultan. Unless the murder of the sultan was the result of a heat-of-the-moment situation, the eunuch who killed the sultan indeed would not have had the courage to kill him without significant support. As the source does not provide details of the structure of the government of the Bengal Sultanate at that time and who held what positions and their relative support base and strengths – concerning the various factions, the positions held by the Habshis, the number of soldiers in the standing army and its command structures, Hindus serving in the administration and the army, etc. – it becomes impossible to make sense of and understand fully or adequately what happened from the accounts given by Ferishta.

The Riyaz provides a similar version and supports the account of Ferishta by stating that Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah’ pursued a liberal policy towards his subject’ and adds that ‘the gates of happiness and comfort were thrown open to the people of Bengal’. It says that one day ‘the eunuch of Fateh Shah… leagued with the paiks and slew Fateh Shah’. After killing the sultan, the eunuch proclaimed himself the sultan. In a similar way as Ferishta, the Riyaz says that the eunuch who murdered the sultan tried to consolidate his position by collecting ‘together eunuchs from all places; and bestowing largesses on low people, won them over to his side’, and through these, he ‘attempted to enhance his rank and power’.

As with the accounts provided by Ferishta, Riyaz’s version also does not help us understand why and how what happened, as no contexts have been provided. Either the author of the Riyaz utilised the writings of Ferishta, or both Ferishta and the Riyaz based their accounts on some other materials that were available previously to them, which no longer exist or have not been found yet.

Habshi Ruler I

Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah (1487)

The next phase of the drama was the conflict between Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah and Malik Andil, the Habshi commander, who was said to be the loyal servant of the murdered ruler, Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah. At the time of the murder, according to the Riyaz, Malik Andil was somewhere at the frontiers – although the source does not say anything about which frontiers.

Ferishta and the Riyaz provide a near-identical version of what happened next. In essence, both state that when Malik Andil learnt of the murder of Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah, he wanted to punish the ‘usurper’ eunuch, Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah, and avenge the death of his master. Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah, fearing what Malik Andil might be planning against him, summoned the latter to return to the capital ‘for the purpose of seizing and putting him to death’, according to Ferishta. The Riyaz provides a slightly different, but not contradictory, account of why Malik Andil was summoned to the capital: it was ‘in order to imprison him by means of a trap’. Both sources state that Malik Andil rightly understood the intention of Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah and took steps to pre-empt the latter’s plan.

The contents of the two historical accounts about how the conflict unfolded and how Sultan Shahzada Barkak Shah was killed sound like a fairy tale description of an eyewitness account. As no eye-witness account of the events exists and the historical accounts are not presented as a real fairy-tale, this means that the story with minor variations between the two sources is most likely the result of reports from victorious sides, embellished and developed over time by oral transmitters and writers before being officialised by established historians such as Ferishta more than one hundred years after the events.

According to the sources, Malik Andil entered the capital fully prepared with a large force. On seeing the strength and support of Malik Andil, Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah refrained from executing his plan to capture and kill Malik Andil. Instead, Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah, through overtures of friendliness, invited Andil Malik to the palace and then demanded that he place his hands on the Quran and promise never to injure him, in one account, and not to kill him, according to another version. Malik Andil responded to that demand by answering that as long as Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah was on the throne, he would not harm him. According to how Ferishta and the Riyaz interpreted the conversations between the sultan and the commander, Malik Andil did not promise not ever to kill the sultan – whom he considered to be an illegitimate ruler of Bengal – but only that he would not kill him while he was on the throne. Ferishta says that Malik Andil’s promise was specific, saying to Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah that ‘since he had ascended the throne, he would never lay hands on him while he “filled that seat”, which only meant literally sitting on the throne. If Malik Andil did indeed make this promise, then the way the story has been narrated means that – and most probably so, otherwise the immediate outcome would not have been amicable – he and Sultan Sahzada Barbak Shah must have understood two different things from Malik Andil’s promise. Whereas Malik Andil only meant while sitting literally on the chair of the throne, Sultan Shahzada understood it to be while he was the ruler of the Bengal Sultanate. If the latter were the case, then formally, at least, Malik Andil would have wanted Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah to understand that he meant while on the throne, but with some doubt to create fear in the sultan that it might be, literally, on the chair of the throne.

In any case, whether the story is fully or partially true, the way that the promise has been phrased in the historical writings, no doubt, has been designed or evolved to promote and maintain an image of Malik Andil as a man of honesty and integrity. If Malik Andil were seen to have promised something to someone holding the Quran that he had no intention of keeping, which he broke later by killing the sultan, his action would have been not only unjustifiable but condemnable. It would have been unthinkable for someone to do so in a society that was governed and justified by Islamic principles, the top of which consisted of having total respect for the Quran. The story as narrated, through semantic ambiguities, justifies the killing of Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah by Malik Andil. It clears his conscience of any wrongdoing against the Quran and induces people to form a favourable judgment about his conduct in killing Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah.

Although Malik Andil swore on the Quran that he would not harm Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah, he, nevertheless, planned to avenge the killing of Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah, the previous sultan whose loyal servant he was to the end. His efforts in this regard were said to have made some inroads into winning the confidence and support of some of the personal guards of Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah. As such, in one evening, Malik Andil was secretly let into the palace, who then ‘entered the harem to kill the eunuch’ sultan. According to the Riyaz, ‘when he found the latter asleep on the throne’, due to being intoxicated by ‘excessive indulgence in liquor’, Malik Andil ‘hesitated, on recollecting his vow’, made while holding the Quran, not to harm him while sitting on the throne.

However, without providing any other details, the sources state that while Malik Andil was inside the harem, Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah suddenly fell on the floor from the throne after turning on his side. On seeing him on the floor, Malik Andil was said to have felt that, as the sultan was no longer sitting on the throne, the pledge that he made holding the Quran did not apply anymore, so he used his sword to kill him. However, he only succeeded in cutting parts of his body. But as the eunuch sultan was not fatally injured and as he was the ‘stouter man of the two threw the latter’, a physical struggle ensued. During the hand-to-hand fight between the two men, Malik Andil found himself underneath the sultan, whose hands were on his throat while he held the sultan’s hair. The room became dark as the physical movements of the two men struggling caused the light to fall and get extinguished under them. At that time, a Turk named Yugrush Khan, being called by Malik Andil for assistance, came in with several Abyssinians to aid him. Unbelievably, the Riyaz provides a direct quotation from the mouth of Malik Andil during the struggle on the floor while Sultan Shazada Barbak Shah was on top of him.

“I am holding the hair of the eunuch’s head, and he is so broad and robust, that his body has become in a way my shield; do not hesitate to strike with your sword, since it will not penetrate through, and even if it does, it does not matter; for I and hundred thousand like me can die in avenging the death of our late master.”

I will not go into further details on how the story unfolded, as told by both Ferishta and the Riyaz, but what followed was a swift end of Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah’s life that night.

After the death and removal of Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah, Malik Andil summoned the vizier (prime minister) to a council to discuss with the nobles to elect a regent and enthrone the infant son of the murdered sultan. However, the nobles were hesitant as the child was still too young, about two years old, so they, as a group, went to the house of the late sultan’s widow to discuss with the dowager queen about the succession issue. Bizarrely, the Riyaz provides another direct quotation, this time from the widowed queen.

“I have made a vow to God that I would bestow the kingdom on the person who kills the murderer of Fateh Shah.”

At first, Andil Malik was hesitant to accept the position of the widowed queen, but later, he accepted it as the nobles were also in favour of him becoming the sultan. The Riyaz reports that when a unanimous assembly of noblemen at the court supported what the dowager queen wanted, Malik Andil ascended the throne.

According to Ferishta, the eunuch sultan, Shahzada Barbak Shah, ruled for just two months. In contrast, Riyaz mentions three different versions but does not commit to any of them: two and a half months, six months and eight months. The Riyaz concludes the chapter on habshis in his book by stating that “God only knows the truth”, concerning the true period of the rule of the eunuch sultan.

What do modern historians say about this? According to Heinrich Blochmann in the Geography and History of Bengal: Muhammedan Period, he was not sure but referred to the three possible periods as provided by Riyaz.

Blochman was among the first British officers in Bengal who utilised coins and inscriptions to complement and correct historical writings, particularly dates, names of rulers, the extent of territories, etc. One of the reasons why Blochmann did not further analyse the three possible dates provided by the Riyaz and one by Ferishta was most probably because he did not have any coins from that period when he was undertaking his work. In the book, as named above, he notes in the table of coins and inscriptions that none were available. When Jadunath Saker edited ‘The History of Bengal’, volume 2, in 1948, Dr A B M Habibullah wrote that no coins or inscriptions of the period were available to him:

“How long the eunuch’s sovereignty lasted, it is difficult to say, for no epigraphic or numismatic record of his reign has come to light.”

However, luckily, some coins of Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah’s rule have come to light recently. According to Syed Ejaz Hussain in The Bengal Sultanate, “it appears that the rule was … about six months”.

In the coins, he was described as “Ghiyas-ud-duniya waddin Abul Muzaffar Barbak Shah Al-Sultan (assister of the world and religion, the father of the victorious, Barbak Shah, the King”. Syed Ejaz Hussain says that the coins of this sultan were issued at three different mints – Fathabad, Dar-ul-zarb and Khazana – which indicate that his support base was wider than the impression created by Ferishta and the Riyaz. If the dates in the coins are correct, most probably they are because of the dates on the coins of the next Abyssinian ruler when Malik Andil became Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah, they indicate the start of the next phase of the Habshi rule of Bengal.

Habshi Ruler II

Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah (1487-90)

Although Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah ruled for nearly three years, more than five times that of Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah, not much has been written on his reign by Ferishta or the Riyaz. He was said to have been a good king who brought justice and stability to the Sultanate, carried out many public works and undertook initiatives to improve the conditions of people experiencing poverty. At least, initially, he was popular. He was also admired and feared. Though neither Ferishta nor Riyaz includes in their accounts details of public works that were said to have been part of his legacy, Riyaz mentions that “a mosque, a tower and a reservoir in the city of Gaur, were erected by him”.

Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah’s levels of public expenditures, especially concerning the poor, alarmed many officers and nobles at the court. The Riyaz has provided an example of that in quotation form.

“It is said that on one occasion in one day he bestowed on the poor one lak of rupees. The members of Government did not like this lavishness, and used to say to one another: “This Abyssinian does not appreciate the value of money which has fallen into his hands, without toil and labour. We ought to set about discovering a means by which he might be taught the value of money, and to withhold his hands from useless extravagance and lavishness.” Then they collected that treasure on the floor, that the king might behold it with his own eyes, and appreciating its value, might attach value to it. When the king saw the treasure, he enquired: “Why is this treasure left in this place?” The members of Government said: “This is the same treasure that you allotted to the poor.” The king said: “How can this amount suffice? Add another lak to it.” The members of the Government, getting confounded, distributed the treasure amongst the beggars.”

The Riyaz says that he died after three years of rule and that the cause of death, from the most reliable account, was that he was killed by the palace Paiks. Strangely, as mentioned earlier, Riyaz manages to quote direct conversations between Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah and Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah – first, while the former was making a promise to the latter, holding the Quran, not harm or kill him, and later, during the physical struggles between them while struggling on the floor. The accounts of Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah’s final moments before Malik Andil killed him include descriptions of the scene, direct conversations between them and how Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah was enthroned. However, no information is provided on the circumstances of his death.

Based on coins and inscriptions during the rule of Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah, Syed Ezaz Hussain concludes that he ruled for about three years from 1488 to 1491.

His coins found to date were issued from the following mints: Muhammadabad, Fathabad, Khazana and Dar-ul-zarb. In total, six inscriptions relating to Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah have been listed, found in Mymensingh, Gaur, Burdan, Murshidabad, Malda and Dinajpur. Based on the coins, the sultan called himself Saif-ud-duniya wadin Abul Muzaffar Firuz Shah Al-Sultan (the sword of the world, the father of the victorious, Firuz Shah, the King).

Firuz Minar

The Firuz Minar in Gaur is usually associated with the ‘tower’ mentioned by the Riyaz. Some commentators have said that, like the Qutub Minar in Delhi, the Firuz Minar was also built to symbolise war victory. However, no wars or victories achieved by Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah have been chronicled by either Ferishta or Riyaz or anyone else. Another point to note is that the building of the Firuz Minar was supposed to have begun in 1485, according to some sources, which was about two years before this sultan was enthroned. If it were true that the construction of the Firuz Minar was started in 1485, then it would mean that Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah commissioned the project. The construction works were continued and completed during the time of Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah. The available information I have seen so far does not show definitively that this sultan constructed the Firuz Minar.

Habshi ruler III

Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah (1490-91)

When Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah was killed or died a natural death in 1490, a child became the new sultan, whose age does not appear in the historical sources. He became known as Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah. According to Ferishta, Jalaluddin Fateh Shah, the last Ilyas Shahi sultan, was his father. If the child placed on the throne were indeed the son of Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah, his age would have been around five when he became the sultan. Three years earlier, when he was just two years old, the court nobles considered him too young to be the sultan. The child’s mother, the dowager queen, also opposed her infant son ascending the throne. Why would just three years later, at the age of five, he would be considered old enough to become the new sultan?

In contrast, Riyaz says that when “Firuz Shah passed to the secret-house of non-existence, the nobles and the ministers placed on the throne his eldest son, Mahmud. On the one hand, if his son had been of a rightful age to become the sultan, then the succession would have been simpler if the cause of the death of Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah had been natural. But if it were a murder that killed him, then those who killed him would have made efforts to stop his son, Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah, from ascending the throne. No power struggles after the death of Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah have been recorded. Therefore, the most probable cause of Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah’s death was either disease, accident or other natural causes.

However, based on the study of ‘recently discovered coins’, Syed Ejaz Hussain concludes that Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah was the son of Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah. Ezaz bases his conclusion on the wordings on the coins when describing Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah: “Qutb-ud-duniya wadin Abul Mujahid Mahmud Shah Al-Sultan ibn Firuz Shah Al-Sultan (pole-star of the world and religion, the father of the crusader victorious, Mahmud Shah, the King, son of Firuz Shah, the King)”.

Even though Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah has been described as the son of Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah in the coins, it is still possible that he was not.

As a young child when he ascended the throne, Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah’s role in decision making was likely minimal. The prime minister, Habash Khan, as the regent and de facto sultan, would have been the key decision-maker, including the decision to name Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah as the father of Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah on coins issued in the new sultan’s name.

According to some accounts, Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah treated the infant son of his master, Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah, as if he were his own son and might have even adopted him. If that were the case, then describing Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah as the son of Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah would not cause any problems. Another reason why Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah may not have been the biological son of Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah was that the late sultan was possibly a eunuch. No mention of him being a eunuch is recorded, however. If he did indeed have a son, then he would have been, most probably, married to an Indian lady – as very few Abyssinian women have been recorded to have been brought to India originally as slaves – whether from Bengal or while in Gujarat or Deccan from where he might have been recruited before coming to Bengal.

As the new sultan was young, he was unlikely to have been actively engaged in running the administration of the Sultanate. Like in many other places around the world, when a young child inherited the throne, a regent was normally elected or appointed to run the affairs of the government on behalf of the child while underage, with support from a council of nobles and officers. Whether he was the son of Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah or Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah, as he was young, a regent was placed in charge of the government. His name was Habash Khan.

Without informing the age of the child sultan, Riyaz complains that Habash Khan, described as a slave, became the administrative-general of financial and administrative affairs. And that ‘his influence so completely pervaded all affairs of government, that, except a bare title, nothing of sovereignty was left to Mahmud Shah’. It was said that this continued to be the affairs of the day until another Abyssinian named Sidi Badr Diwana, also described as a slave, ‘despairing of his way’, killed Habash Khan and became the administrator of the affairs of the government. Then, after a short while, Sidi Badr Diwana conspired with the palace paiks, killed Sultan Mahmud Shah, and established himself on the throne.

A slightly different story has been told by Ferishta, who claimed that the move by Sidi Badr Diwana against Habash Khan was because the latter was planning to capture the throne for himself. When Sidi Badr Diwana discovered Habash Khan’s plans, he killed him. He also killed the young sultan a little later and established himself on the throne. Based on the timing of events in Ferishta’s accounts, it appears that Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah was on the throne for just over six months, while Riyaz stated that his reign lasted one year. According to an analysis of relevant coins by Syed Ejaz Hussain, Sultan Mahmud Shah’s reign lasted only for a few months.

Although the rules of Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah and Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah were very short, their respective periods witnessed instability, rivalry, conspiracies and their killings by individuals who subsequently became sultans (Saifuddin Firuz Shah and Muzaffar Shah, respectively), each ruling the Sultanate between two and three years. Historical records include little details about their activities, achievements, successes and failures. In contrast to the very little information on the time that Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah ruled, there exist more details on Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah, which describes some of his policies, the impacts he had and the final battle that led to his death and overthrow by his prime minister, who established himself on the throne as Sultan Alauddin Hussain Shah.

Habshi ruler IV

Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah (1491-94)

Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah, described as a slave, has a different reputation than Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah. In contrast to the latter, described as a just, wise and caring ruler, especially concerning the poor, the former has been painted as blood-thirsty, short-sighted, cruel and unwise. The Riyaz states that he killed ‘many of the learned and the pious and the nobility of the city, and also killed the infidel Rajas who were opposed to the sovereigns of Bengal’. Other unwise acts attributed to him include cutting the pay of soldiers to build up the treasury for which he also ‘committed oppressions in the collection of revenue’. Ferishta adds that those that Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah killed were ‘whose principles induced them to adhere closely to the tenets of the orthodox faith’. He also states that his Prime Minister, Syed Hussain Sharif, encouraged the sultan to disband the greater part of his standing army, which caused the reduction of the number of soldiers on service so low that many of the army chiefs quit their jobs. Ferishta suggests that the activities of Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah that made him very unpopular and hated were engineered by the prime minister, deliberately designed to tarnish the sultan.

With the increase in Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah’s unpopularity and the many plots hatched against him by some nobles, army chiefs and officers, the prime minister decided to join hands with the rebels to oust the sultan from power. The move of the rebel group against the sultan at Gaur palace did not result in an immediate defeat or victory for the rebels. Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah was said to have barricaded himself at the palace with five thousand Abyssinians and thirty thousand Afghan and Bengali forces. Hand-to-hand, swords and arrows were parts of the methods of warfare employed by both sides. According to one report, the battle raged for about four days, and according to another, it lasted four months.

Many people on both sides were said to have been killed when one side made forward sorties against the other and vice versa. When the sultan’s forces captured members of the rebel group, they were brought to the sultan, who personally killed them. The total number of rebels personally killed by Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah was said to be four thousand. One report claims that the total number of dead during the four-month battle covering both sides was about one hundred and twenty thousand.

Finally, after a major push by the rebels against the besieged palace, the rebels became victorious, and Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah, with many of his relatives, was killed. According to Ferishta, the end part of the battle came when the prime minister gained the confidence of the palace paiks. They let him enter the palace with eleven others, who then killed Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah. After that, the prime minister, Syed Hussain Sharif, was installed on the throne and became the new sultan.

Soon after the killing of Sultan Muzaffar Shah, according to Riyaz, a council of nobles was called. There, the nobles supported Syed Hussain Sharif’s wish to become the sultan after he had answered their questions satisfactorily. Again, Riyaz managed to find a direct quotation from the council session. Syed Hussain Sharif was asked, “If we elect you king, in what way will you conduct yourself towards us?” To this, he answered, “I will meet all your wishes, and immediately I will allot to you whatever may be found over-ground in the city, whilst all that is underground I will appropriate to myself.” This was said to have given a licence to the nobles and soldiers to pillage the city – the city of Gaur that Riyaz described as eclipsing Cairo in terms of wealth. The new sultan, who was enthroned in 1494, became known as Sultan Alauddin Hussain Shah. However, after a few days of ascending the throne, the sultan forbade the continuing pillaging of the city. When some did not adhere to his edict, he killed about twelve thousand plunderers, which brought the pillaging to an end.

According to Ferishta, Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah’s rule was three years, whereas Riyaz says it was three years and five months. However, Syed Ejaz Hussain, analysing relevant coins and inscriptions, including newly discovered ones, concludes that Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah ruled for two years and a few months.

He also points out that some coins indicate that he led wars of conquest and achieved some victories, including territorial advances. If true, this would show that, at least for a while, the largely non-Abyssinian army of the Bengal Sultanate was loyal to the Abyssinian sultan. As such, there could not have existed a general feeling of anti-Abyssinians or against the rule by Abyssinians among other groups in Bengal, particularly in the city of Gaur.

The new sultan, who was said to have been of Arab descent, founded a new ruling dynasty called the Hussain Shahi Dynasty. During its forty-year rule, it produced the rule of four sultans until the Afghan Sher Shah ended the dynasty when he defeated the last Hussain Shahi ruler, Sultan Mahmud Shah, in 1538.

During the early years of the Hussain Shahi dynasty, the sultan took several decisive steps to deal with the recent problems of instability and bloodshed within the sultanate. The palace paik guards that were responsible for helping to kill at least three of the four Abyssinian rulers, if not all the four, were said to have been disbanded. The Riyaz also claims that the sultan ‘also expelled totally the Abyssinians from his entire dominions. Further, as the expelled Abyssinians were also not welcomed in Jaunpur, because they were ‘notorious for their wickedness, regicides and infamous conduct’, they ‘went to Gujrat and the Dakhin (Deccan)’.

Accounts of foreigners

By the time Sultan Alauddin Hussain Shah became the ruler in 1494, many of the Abyssinians who started to come to Bengal from the time of Sultan Rukunuddin Barbak Shah (1459-74) would have been in their forties, fifties, sixties or even seventies if some of them managed to survive that long. Many of them would have been married – except those who were eunuchs – to local women with children, as was the case in the Deccan between Abyssinian slave soldiers/personals and local Indian women. Some of the Abyssinians would have also been freed slaves – through manumission given by their masters or upon the death of those who owned them. Some became members of the nobility, such as Malik Andil, who was described as a loyal commander and a respected nobleman and became Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah in 1487. The idea that the Abyssinians were totally expelled from Bengal seems hard to believe, especially as they did not act as one body but were themselves divided and either supported by or were also allied to non-Abyssinian factions.

During the war between the Abyssinian Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah’s forces and that of the Arabian Syed Hussain Sharif, a larger number of Afghans and local Bengali forces were said to have fought on the side of the relatively smaller number of Abyssinians supporting the sultan. The forces opposing the Abyssinian Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah must have also included Abyssinians, as there was a large Abyssinian presence in the military during that time. Many of them were opposed to Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah, who killed the previous child sultan and his prime minister, who were both Abyssinians. However, the child sultan might have been from mixed Abyssinian-Indian heritage or descended from the Ilyas Shahis. Syed Ezaz Hussain thinks that Riyaz may have been wrong in the view that the Abyssinians were, in their totality, expelled from Bengal based on a stone inscription of Hussain Shah’s records, according to which it was ‘one Malik Kafur, who built a mosque in 1504-5’. Malik Kafu was an Abyssinian.

Although coins and inscriptions provide valuable details regarding dates, names, occasions and deeds of rulers and important people, they do not include details of the society in question and its compositions. So, they cannot be relied on to learn, for example, whether Riyaz was right to conclude that the Abyssinians were totally expelled from Bengal. And, if they had indeed been expelled or encouraged to leave Bengal, then it might have taken a more extended period than happening immediately and quickly after Hussain Shah became the sultan in 1494.

What kind of accounts exist of near-contemporary foreign visitors to Bengal or foreigners who wrote from nearby places such as Melaka and Goa, based on reports they received from others? The nearest first-hand account of an actual foreign visitor to Bengal and the city of Gaur was by an Italian named Ludovico Di Verthama. His book, The Travels of Ludovico Di Verthama, is based on his travels in that part of the world during 1503-08. His personal perspective adds a unique connection to history, as he includes interesting and remarkable information on the country of Bengal, the economy, its cultures, the attires of the people, the nature of the city, etc. He also believed that the capital city of Bengal was ‘the best place in the world, that is, for living in’.

Although his records include nothing about Abyssinians living in Gaur, they provide a detailed account of the Armenian Christians he met in the city. Neither does he name any other groups or inhabitants of Gaur except to say that the sultan of the country was a ‘Moor’ who maintains ‘two hundred thousand men for battle on foot and on horse; and they are all Mohammedans’. However, when he talks about the exports of Bengal, he says, “Fifty ships are laden every year in this place with cotton and silk stuffs, which stuffs are these, that is to say, bairam, namone, lizati, ciantar, doazar, and sinabaff. These same stuffs go through all Turkey, through Suria, through Persia, through Arabia Felix, through Ethiopia, and through all India”. Why would he include Ethiopia as a destination for some of the goods of Bengal if Abyssinians were totally banished from the sultanate?

‘The Book of Duarte Barbosa’, written by Duarte Barbosa, published in 1518 from accounts written a few years earlier without ever visiting Bengal, contains interesting information on the country. His accounts are based on what he had heard from others and include details about the people of Bengal, their attires, the economy and so on. He also mentions Abyssinians in his list of people as examples of ‘strangers from many lands, such as Arabs, Persians, Abexys’ who live in Bengal. However, he does not discuss anything in detail about the Abyssinians in Bengal.

Between the time of Verthama and Barbosa appeared Tom Pires, who wrote detailed accounts of many places in Asia, including Bengal, without ever visiting the place. And incredibly, he makes some strange conclusions about the people of Bengal.

He was in Asia in an official capacity, collecting intelligence and valuable information about places, trade, manufactures, natural resources, rulers, powers, supporters of ruling groups, etc. At that time, the Portuguese were involved in their Indian Ocean empire-building efforts. They were engaged in gathering and collecting information to understand the power and economic structures of places in Asia and the strengths and dynamics of places, kingdoms and cities.

Tom Pires got to Melaka soon after the city state’s conquest by the Portuguese in 1511, and much of what he wrote about Bengal, its economy and its diverse population must have been gathered from merchants and visitors to Melaka who were either directly from Bengal or had long years of experience of trade with Bengal. Although the first official Portuguese visit to Bengal took place in 1517, it is believed that individual merchants and adventurers used local vessels from some of the Portuguese settlements that the Portuguese had already established to visit Bengal. This group may also have been a source of information on Bengal for Tom Pires.

Strangely, Tom Pires starts his chapter on Bengal by claiming that

“The Bengalis are great merchants and very independent, brought up to trade. They are domestic. All the merchants are false”.

Unless something is missing through translation, I fail to understand what he is trying to say. He then says, “The Bengalees are merchants with large fortunes, men sail in junks”. Perhaps he observed some such junk arriving in Melaka and unloading their goods, and he conversed with some of the officials, traders and sailors.

“A large number of Parsees, Rumes, Turks, and Arabs, and merchants from Chaul, Dabhol and Goa, live in Bengal. The land is very productive of many foodstuffs; meat, fish, wheat, and (all) cheap. The king is a Moor, a warrior. He has great renown among the Moors. The people who govern the kingdom are Abyssinians. These are looked upon as knights; they are greatly esteemed; they wait on the kings in their apartments. The chief among them are eunuchs and these come to be kings and great lords in the kingdom. Those who are not eunuchs are fighting men. After the king it is to these people that the kingdom is obedient from fear. They are more in the habits of having eunuchs in Bengal than any other part of the world. A great many of them are eunuchs. Most of the Bengalees are sleek, handsome black men, more sharp-witted than the men of any other known races.

They have now been following the Pase (Pace) practice in Bengal for seventy-four years, that whoever kills the king becomes the king. They hold and believe that no one can kill the king without the consent of God, and he therefore becomes the king; and in this way the kings last a short time. From that time up to now it has always been Abyssinians – those who are very near to the king – who have reigned. This is done such a way that there is no surprise in the kingdom. The merchants live in peace. It is already the custom. Formerly, it was not done in this way, but from father to son. They borrowed this practice from Pase and they keep strictly to it.”

The detailed account of Tom Pires is near-contemporary as compared to both Ferishta and the Riyaz, who wrote more than one hundred years and nearly three hundred years, respectively, after the end of the ‘Habshi rule of Bengal in 1494. Whereas Tom Pires’s account is based on reports that he had heard from others, Ferishta and Riyaz also used accounts of the Habshi rule circulating during their days. As the accounts of both Ferishta and the Riyaz were near-identical, they both, no doubt, relied on long-held accounts in written and oral forms when they were writing their pieces.

Had there not been any Abyssinians in Bengal during the time of Tom Pires, it is hardly believable that he would have made up a false story or that visitors and traders from Bengal to Melaka would have told him something false. Suppose the Abyssinians were indeed expelled from Bengal soon after the establishment of the Hussain Shahi rule. In that case, it is more likely that what Tom Pires wrote was based on confusion about timings and several things that happened in the recent past.

The Abyssinians were introduced into Bengal in large numbers from around 1460 onwards, and their power and influence grew gradually. This eventually led several individuals from an Abyssinian background to become the rulers of the Sultanate. The decline of the Bengal Abyssinians took place soon after the defeat and death of Sultan Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah. Were they all expelled immediately and totally from Bengal after the short-lived ‘Habshi rule’ or did they gradually disappear over some time through migrating out and inter-marriages with local women? It is more likely that not many new, if any, Abyssinians came to Bengal after 1494. And among those who were already there, some could have left the country quite quickly, while others disappeared slowly from Bengal through death and intermarriages with local women.

Slave Sultans

The Muslim rule that began in northern India from the late 12th Century with the invasion of Muizudin Muhammad Ghori, a Turk, was centred in Delhi. By the early 13th Century, the Delhi Sultanate was established by Qutubuddin Aibak after the death of his master Muizudin Muhammad Ghori in 1206. Qutubuddin Aibak was a slave of Muizudin Muhammad Ghori who placed the conquered Indian territory under his governorship. At first, he appointed Qutubuddin Aibak as the governor, who ruled the conquered territories on behalf of his master. But after the death of Muizudin Muhammad Ghori in 1206, Qutubuddin Aibak became the ruler. After a brief power struggle, and on receiving official notification of manumission, he was accepted as a legitimate sultan. When he died in 1210, another freed slave of the Muizudin Muhammad Ghori, Shamsuddin Iltutmish, after another short power struggle, became the sultan and ruled until 1236.

From the time of Muizudin Muhammad Ghori’s conquest of northern India and until the death of Sultan Ghyasuddin Balban in 1287, that period of the Delhi Sultanate has been described as the rule of slave sultans or mamluks. During that period, slaves were rulers, army commanders, troops and state officials, and occupied a range of positions in the Sultanate.

From early on in the Delhi Sultanate, Habshi slaves were also a part of the machinery. Their influence was extremely limited at that time, except when Sultan Jalaluddin Razia became the ruler, the first female sultan, in 1236. A particular Habshi, called Jamaluddin Yaqut, described as a slave-amir, acquired high-levels of influence in the state machinery and became a close adviser and protector of Sultan Jalaluddin Razia. This situation did not go well with the Turkish dominated power structure of the time. They opposed a woman sultan and the influence that an Abyssinian slave was having on the sultan. Sultan Jalaluddin Razia’s dependence on the Abyssinian for advice and protection was considered too much by the Turkish nobility to accept, which could not go unanswered.

According to historical documents and their interpretations by modern scholars, most of the slaves serving in the Delhi Sultanate were from a Turkish ethnic background. They mostly consisted of military slaves, brought from their ancestral homes in central Asian steps to India to serve the rulers of the Delhi Sultanate. Most of the early rulers of Bengal Sultanate were slave governors appointed by Delhi sultans, except for a brief Khalji period (1205-1227) that followed Bakhtiar Khilji’s initial conquest of Bengal, when several free ethnic Turks became rulers. From the late 13th Century to the short-lived Habshi rule of Bengal (1487-94) there were no other slave rulers of Bengal. The Habshi rulers of Bengal could not have been slaves when they ruled, although when they first came to India, they were slaves.

It has been a difficult task to develop an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon of ‘slave rule’ in both the Delhi and Bengal sultanates. How was it possible for some of the slaves that were purchased in faraway places and brought to India to become rulers? The second slave ruler of the Delhi Sultanate, Shamsuddin Iltutmish, was said to have been questioned by Islamic jurists when he took power about his slave status as a slave could not become a ruler. Sultan Shamsuddin Iltutmish produced documents to prove his manumission – granted freedom by his master Muizuddin Muhammad Ghori, through his slave Qutubuddin Aibak.

Both in Delhi and Deccan sultanates, slaves played many roles in the state machinery. One of the main functions of the slaves was to serve in the military. Many of them subsequently became important army commanders. Some slave commanders were said to have received manumission when their masters died, while others became free individuals when they were released from bondage by their owners. When a master died, his slaves did not have an automatic right to become manumitted. An offspring of a master possessed hereditary rights to inherit the properties of the deceased, which included slaves owned by the master.

The materials that I have studied so far have not made things crystal clear in my mind about manumission. There were likely many different outcomes in legal terms concerning how slaves achieved manumission under different situations. Perhaps, there were creative contexts-based rulings developed, including in some cases, powerful slave army commanders or rulers might have disregarding prevailing views about manumission and just acted independently. However, regardless of how slavery operated in various sultanates in India, there were many possible ways that slaves could become free. What roles did they play after their manumission and becoming free men? Many Abyssinian slaves in the Deccan, where they were most in-demand, became powerful army commanders. Some of the ex-slaves who became free individuals through manumission continued to serve the rulers as free commanders with the forces under their control who were mostly slave soldiers.

According to Ferishta, eight thousand Habshis were brought to Bengal by Sultan Rukunuddin Barbak Shah (1459-74). But he does not classify them under categories, for example, what proportion were free commanders and slave commanders and the respective forces under them, the number of eunuchs, and so on. Ferishta and the Riyaz provide confusing information about the slave status of the four individuals with a Habshi background that became rulers of the Bengal Sultanate during 1487-94. Presumably, they were all freemen and achieved their manumission previously through any of the possible paths mentioned above. There is also a possibility that some of them were not slaves that directly originated from Abyssinia but could have been born in India from Indian mothers and freed Abyssinian slaves. There is nothing in relevant historical materials that can throw a clear light on this. Unless new information comes to light, there is not much value in further speculation on this issue.

Sultan Shahzada Barbak Shah, the first Abyssinian ruler of Bengal, who ruled for about six months must have had some powerful supporters in the Sultanate, at least at the beginning. Otherwise, he would not have lasted even the short length of time that he did. He was described as a eunuch, but his slave status was not discussed in any of the main sources. As he seems to have been accepted as a legally legitimate sultan for a while, and the fact that no objections linked him to a possible slave status has been documented in historical records, it means that he was most likely a freeman. Otherwise, it is difficult to see how he was treated as a legally legitimate ruler. Many opposed him on other grounds, such as for murdering the previous sultan, becoming cruel and killing many nobles who opposed him.

Malik Andil who became Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah has been described as a ‘premier-nobleman’ by the Riyaz. There is no discussion about his previous or current slave status by Ferishta or the Riyaz. Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah was either the son of Sultan Jalaluddin Fateh Shah or Sultan Saifuddin Firuz Shah – his slave status is not discussed in any of the historical documents. However, Habash Khan, who was entrusted to look after the child sultan, who became the administrative-general of financial and administrative affairs, was described as a slave by both Ferishta and the Riyaz. Sidi Badr Diwana, who became Sultan Muzaffar Shah after murdering Sultan Qutubuddin Mahmud Shah, has been described as a slave by Ferishta but not by the Riyaz.

As these four individuals were all sultans for various lengths of time with support from some wider sections of society, rather than just Abyssinians, they were all likely to have been free men when they assumed power. Based on my current understanding of the slave systems in different sultanates and time periods in India, it is most likely that all the four rulers were free men when they became rulers. But how and when they gained their manumission is not possible to tell. Without manumission, it would not have been possible for any of them to become legitimate, legal sultans, theoretically speaking, as they would have faced a lot of legal barriers to legitimacy.

Missing contexts

Bengal at that time was a Hindu majority land with its divisions, sub-divisions and power structures. Muslims were the ruling class, mostly immigrants – rulers and their families, landlords, nobles, governors, religious leaders and government officials. The Hindus were organised under a caste structure and included landlords and Rajas with powerful forces under their control. They also participated in the Sultanate government structures in various capacities, including holding high positions. The Hindu landlords and rajas provided or deployed armed personnel to support or oppose existing rulers in their struggles against their rivals, depending on the situation on the ground. Ordinary people from many different walks of life belonged to both the Hindu and Muslim communities.

In an article called ‘Scribal elites in Sultanate and Mughal Bengal’ by Kumkum Chatterjee, the author describes some of the roles played by high caste Hindus in the ‘Sultanate and Mughal Bengal’ governments. Although no specific information in this regard is provided concerning the ‘Habshi rule of Bengal’ (1487-94), Kumkum Chatterjee discusses a number of important individuals and the roles that their castes played in the structures of the Sultanate and within society. For example, during the time of Sultan Alauddin Hussain Shah (1494-1519), which followed the short Habshi rule (1487-94), he informs us that Gopinath Basu, who was given the title of Purandar Khan, worked his way through the system when he was ‘entrusted with the affairs of the treasury department’, who ‘then became a naval commander and eventually rose to be the sultan’s chief minister’.

In his book called ‘The Bengal Sultanate: Politics, Economy and Coins’, Syed Ejaz Hussain provide more details of Hindus serving in various capacities in the Bengal Sultanate. ‘Narayan Das was the Personal Physician of Rukm-ud-din Barbak Shah’ (Sultan Rukunuddin Barbak Shah – 1459-74). ‘His son Mukunda Das was the Chief Physician of Hussain Shah’ (1494-1519), whose ‘Chief Secretary was a Brahmin named Sanatan Goswami’. At one time, Sultan Rukunuddin Barbak Shah’s treasurer was Gandharba Rai. Some other examples of positions held by Hindus in the Bengal Sultanate state as provided by Syed Ejaz Hussain is as follows:

“Kader Rai was Bengal’s representative at Tirhut, Bhanddasi Rai was Fort Commander at Ghoraghat and Biswas Rai and Maldhar Basu (entitled Gunaraj Khan) were ministers during the reign of Rukn-ud-din Barbak Shah. Kuladhar also known as Satya Khan and Shobhraj Khan was an important officer under Shams-ud-din Yusuf Shah. Gopal Chakraborty was the Tax Collector at Gaur and Sanatan Goswami was Sakar Mallik or Chief Secretary during the reign of Hussain Shah. Srikanta, brother-in-law of Sanatan, who lived at Hajipur, was assigned the work of purchasing horses by Hussain Shah who had given him three lakh rupees for the purpose. During Nusrat Shah’s reign Basanta Rao (or rai) was the Commander of the Bengal army against Babur.”