During mid-April each year, two or three days preceding and culminating in the Bengali New Year, the three districts of the Chittagong Hill Tracts in Bangladesh – Rangamati, Bandarban and Khagrachari – become a place of colourful festivities. Boisabi is a collective name given to the festivals that take place in the Hill Tracts, coined by combining the first few letters of the festivals of the three main groups who live in the region, namely Boi from Boisu (Tripura), Sa from Sangrai (Marma) and Bi from Bijhu (Chakma).

The incredibly beautiful Chittagong Hill Tracts are home to more than ten different ethnic and indigenous communities, which have their own unique cultural traditions, rich history, diverse costumes, beautiful music, dances, tasty food, and so on. They are Chakma, Marma, Tripura, Tanchangya, Khumi, Mro, Lushai, Khiang, Bawm, Pankhu, Bangoj and Chak, who are often collectively described as Jumma people because of their methods of slash-and-burn crop cultivation on the hills. The Chittagong Hill Tracts are the most culturally and ethnically diverse region within Bangladesh.

Most people in the hills enjoy and participate in the various festivities that take place during the annual mid-April Boisabi programmes, including Bengali settlers who observe the Bengali new year, which happens during the same period and join in the indigenous festivals. The festivals also provide an opportunity for the peoples of the region to showcase the best of their cultures and traditions collectively. Bengalis from the rest of Bangladesh, especially Dhaka, flock to the hill districts in great numbers to experience the distinct cultural practices and expressions of the indigenous and ethnic minority people of the Chittagong Hill Tracts. A few tourists and visitors from outside Bangladesh are also seen enjoying the very welcoming festivities.

Although some aspects of the cultures of the people of Chittagong Hill Tracts have shared elements with Bengali and Indian traditions, their cultures mostly have different roots, forms and expressions. From the point of view of the dress, food, music, dance and religious/communal rituals, the hill people have their own unique and very different ways of life. Bengalis who flock there in great numbers during the festive season do so to witness and experience something very different from what exists in the rest of Bangladesh and considered to be uniquely beautiful and rich.

I first visited the Chittagong Hill Tracts in 1995. At that time, I was quite nervous about going there, but I thought I had to go and see the legendary ‘most beautiful’ place in Bangladesh. I heard from family members, friends and others that the Chittagong Hill Tracts are incredibly beautiful, with high mountains, valleys and enchanting lakes. Some friends from London who visited Rangamati in the 1980s and brought back photographs to London talked highly about their positive experiences. Chakma girls wearing traditional dresses were also a source of attraction for many visitors to the Hill Tracts, promoted by Bangladesh tourism initiatives. When Muhammad Ali, the legendary boxer, visited Bangladesh in Bangladesh in 1977, Rangamati in the Chittagong Hill Tracts was among his many itineraries, where he and his wife Veronica were entertained with a Chakma dance. A documentary film on the visit was made, called ‘Muhammad Ali Goes East: Bangladesh I Love You’, which was shown in mainstream cinema halls across the UK, that included the beauty and dance of the Chittagong Hill Tracts.

I went with a friend from Dhaka to Chittagong in an air-conditioned coach and stayed in the city for one night. On the morning of the next day, we boarded a Rangamati town-bound bus, and the journey took about 2 hours from the city of Chittagong. During the journey, after perhaps about 30 minutes from the start, the landscape began to change completely and dramatically – from low land plain fields to high hills. As the bus moved closer to Rangamati town, I remember seeing some of the tallest mountains in Bangladesh and observing women sitting on the sides of small hills working on their crops. When we got to the town we started to look for a hotel but as we could not find any vacant accommodation quite quickly and out of nervousness due to the conflict, we decided to go back to Chittagong on the same day. We bought our return tickets and went about spending four hours in Rangamati town, where we spent time eating at the Parjatan Hotel, taking a boat ride on the Kaptai Lake, walking on the famous bridge went back to Chittagong City later that day.

One of the reasons why we did not try hard to find available hotels or guest houses was because of our nervousness about the political unrest and the indigenous insurgency taking place in the region since the late 1970s. We did not want to find ourselves without any accommodation after dark. However, the short four-hour stay in Rangamati town and the sightseeing during the journey, including some photographs that I took, brought to my notice how special the hill districts of Chittagong are for Bangladesh. First, I came to know the incredible beauty of the area and then began to realise its enormous economic and tourism potential. Second, I thought that the diverse and beautiful cultures of the hill people could become, potentially a highly enriching experience and a very valuable asset for Bangladesh and sources of development and progress for the indigenous and ethnic minority peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Therefore, I desperately hoped for the conflict in the hills to come to an end so that we, the rest of Bangladesh, could develop better connections and relationships with the region’s people. At that time, I did not understand the background of the conflict and lacked adequate knowledge of the history of the Chittagong Hill Tracts.

My second visit to the Hill Tracts was in April 2011. This time it was a planned undertaking, and there was no anxiety, unlike during my first visit in 1995. The indigenous insurgency officially ended with the signing of a peace accord between the Bangladesh government and representatives of the hill people in 1997. Although not fully implemented, the accord has brought more security and stability to the region, and there are more free flow of people and goods/services between the Hill Tracts and the rest of Bangladesh. Further, in the capital city, Dhaka, more people from the Chittagong Hill Tracts are seen in educational establishments, shopping centres, restaurants, etc., working, studying and participating in the life of the city.

My purpose for visiting this time was to capture some video and still footage of the Boisabi festivals as part of my planned exhibition in London on festivals of indigenous and minority peoples around the world. I arrived in Bandarban town a few days before the start of the Shangrai festival of the Marma community and spent a total of six days in the hill districts, which included a 2-day detour to Rangamati town. During that time, I experienced aspects of the Bijhu festival in Rangamati and more fully the Shangrai festival in Bandarban.

The Boisabi festivals are very significant events for the ethnic minority and indigenous peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, where they bid farewell to the old year and welcome the new one. They celebrate the end of the current year and the beginning of the new year with a series of colourful and lively festivals called, as stated above, Sangrai by the Marma people, Boisuk by the Tripura people and Biju by the Chakmas. While similar in many ways, each group has a few unique aspects to their celebrations, which take place in mid-April every year, depending on the new moon.

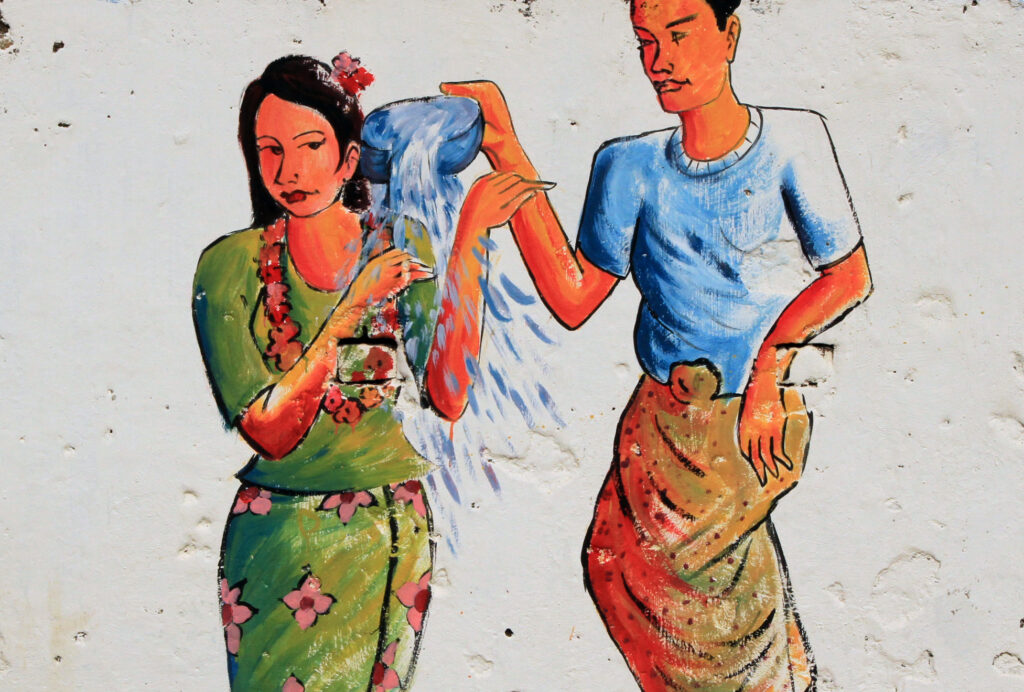

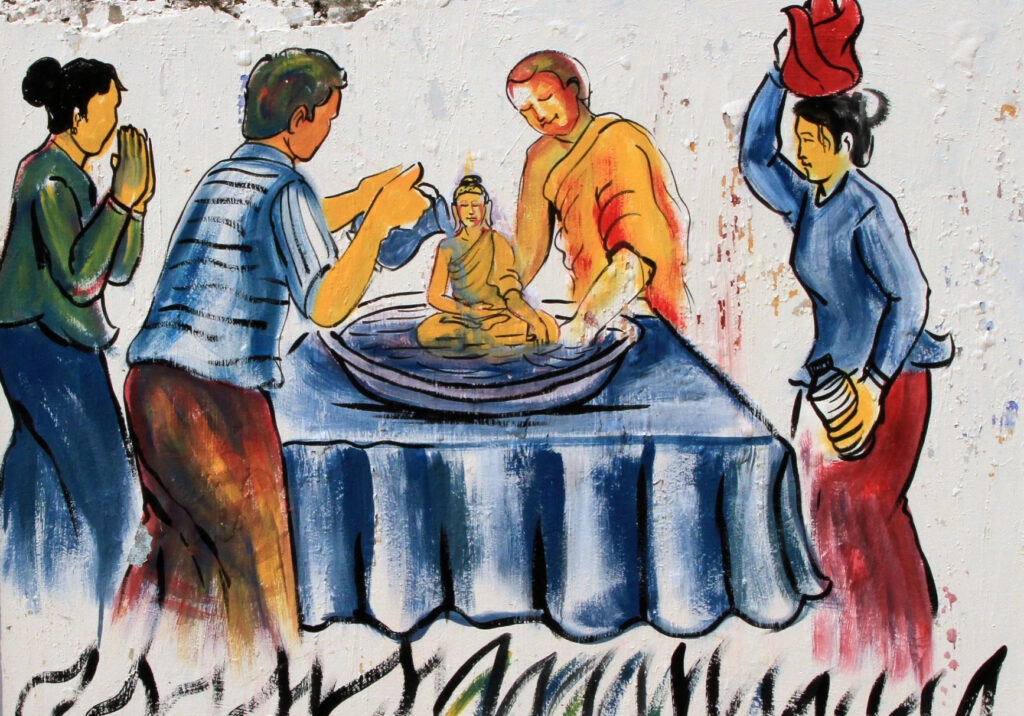

With the Marma people, three days of their four-day festival are spent bidding farewell to the outgoing year, with the fourth focusing on greeting the incoming year. The first, second and third days are called, respectively, Sangrai akya, Sangrai Bak and Sangrai Appyai. On the first day of the festival, both male and female members of the Marmas form a procession to take their statues of Buddha down to the riverfront. There, the statues are washed on a raft with either a mixture of sandalwood and water or milk and water in preparation for re-installing them at the temple or in their shrines at their homes. The following two days, being the last two days of the old year, are spent in a light-hearted celebration called Ri kejek taing, where participants splash each other with water, symbolically washing away all the sorrows and ills of the past year. A similar ceremony is carried out by the Rakhaine (in Cox’s Bazar area), where participants splash each other with coloured water.

The Chakma people enjoy a three-day festival, two of which fall into the outgoing year. The first day is dedicated to celebrations for Phul Bijhu (flower Bijhu), the second for Mul Bijhu and New Year’s Day for Gojyai Pojya. During Phul Bijhu, there is general merrymaking in preparation for the main festival of Mul Bijhu, celebrated on the last day of the outgoing year, on the 30th of the Chaitra month of the Bengali calendar. During the Phul Bijhi, the Chakmas decorate their houses with various colourful flowers, take flowers to worship in the nearby rivers and visit one another’s homes to socialize and eat together. Young girls, distinguished by their blue and red lungis that have been woven on hand-held looms, gather in groups to enjoy each other’s company and wander from house to house at leisure, playing games in the afternoon. On the Mul Bijhu, various kinds of food are made in every Chakma house and are served to guests, particularly the delicious panchan, a mixed dish made of five vegetables and many cakes. The third day is Gojya-pojya din, meaning taking rest and the day is also celebrated with traditional cultural activities like folk songs (Gengkhuli Geet), dance and drama (Chakma Tatak).

The Tripura community, in addition to spending time visiting each other’s homes and have traditional foods such as panchan, they enjoy Goraia dance, with between 10 and 100 artists participating in the dance, which depicts their daily lives and the processes of Jhum cultivation on the hillsides of Chittagong. Throughout the Chittagong Hills Tracts, the first day of the new year is greeted with merriment and the hope for a prosperous and trouble-free year ahead.

Although the Boisabi festivals are a very joyous festive time for most people in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, there is a deep sense of unease among the ethnic and indigenous populations of the hill districts about the rapid demographic changes taking place. The recent population changes of the various groups residing in the Chittagong Hill Tracts are provided in the table below:

| Year | Hill people | Bengali |

| 1872 | 61,957 | 1,097 |

| 1901 | 113,074 | 8,762 |

| 1959 | 260,517 | 27,171 |

| 1981 | 441,796 | 304,873 |

| 1991 | 500,190 | 474,255 |

Currently, the Bengali population of the Chittagong Hill Tracts have become the majority. The shift of Bengalis from a very small minority in the early 1960s to nearly half the total number by 1991 was clearly a massive shift and an unprecedented change for the people who have lived there for generations. Most of the population changes have taken place since the birth of Bangladesh.

The beautiful and inspirational birth of Bangladesh soon became a nightmare for the people of the Chittagong Hill Tracts. A refusal by the then Bangladesh government to recognise the hill people’s separate identities, including attempts made to encourage and pressure the ethnic minority and indigenous peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts to become (bizarrely) ethnic Bengalis triggered a process of alienation, insurgency, militarisation, violence, planned settlements of Bengalis into the Hill Tracts to engineer a population change to, partly, ensure that the people of the area never ever dream of separation and independence from Bangladesh.

During my 2011 visit to Bandarban, I talked to several people and saw in the faces of many local Chakmas, Marmas and others a deep sense of sadness and fear at the continued loss of their traditional lands to incoming Bengalis and their inability to dream of a better future. Political problems and violence between Bengali settlers and the local ethnic minority and indigenous peoples have continued, albeit at a lower level since the signing of the Peace Accord in 1997, except for periodic eruptions of major disturbances. What would happen to their traditions and identities as distinct proud peoples with the continuous shrinking of, in proportion, their population? Anxieties, fear, sadness, frustrations and unease run very deep in the beautiful lands of the Chittagong Hill Tracts.

I wanted to develop a better understanding of the meanings and purpose behind the activities of the Boisabi festivals before completing the write-up for this exhibition.

Rumana Hashem, a brave, inspirational lady who did some work on the Chittagong Hill Tracts, introduced me to Jewell Samong Prue, a Marma young man who lived in London around the time I was organising my Powers of Festivals’ exhibition in 2012. I first met him at the ground floor food court of Westfield Shopping Centre in Stratford, London, and explained to him about my exhibition and that I needed information and explanations about some pictures of the Boisabi festivals that I brought back from my visit in April 2011. He was very happy to help and explained many important things about the Hill Tracts, the people, culture, history and politics, and agreed to provide more information later. In fact, he ended up being more helpful than I originally expected, and he must have worked very hard in this regard. I am very grateful for his help.

When I asked him about the nature of the impacts of the festivals on the people, he said that the ‘Boi- Sa- Bi celebration has a ‘great impact on the social life of the indigenous peoples in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. This is the time to forget all sorrows and the failure of the past year and wish people grace and happiness for the upcoming new year’. He informed me that from his childhood, he grew up seeing the colourful celebrations held every year. However, he went on to point out that in recent years although the festivities are as enjoyable as before, the political conflict between the Bangladesh government and the indigenous communities during the last few decades have caused the festive happiness to fade away very quickly. As a member of the Marma indigenous community, he finds the water festival to be the most attractive event during the celebration. ‘Many races and colours of the various communities in the Chittagong Hill Tracts gather together and enjoy their most popular festival’.

The Sangrai festival in Bandarban consists of a major parade (rally) by various indigenous and ethnic minority communities of the Chittagong Hill Tracts. During the festive period, I witnessed Pita Uthshab (cake festival); wrestling competition; various traditional games/sports played by children and adults; children’s poetry recitation and painting competition; the Pobitra Buddha Snan, where they symbolically bathe statues of the Buddha; children throwing water at each other and at adults; the famous organised water fights between young men and women dressed to look good; children spending a whole night making cakes and sweets for Buddhist priests, which they present to them the following morning. I was informed that the children participating in the cake-making nigh long event are kept awake by offering regular cups of strong tea throughout the night.

‘During my short stay in April 2011, the beauty of the Chittagong Hill Tracts and the diverse cultures of the various groups in the region kept growing on me. I felt quite sad leaving the area just after six days as a few more days would have given me an opportunity to better understand local issues, feelings, meanings, etc., appreciate and enjoy more of what the region has to offer.’

On reflection, it is clear to me that the rich cultures of the hill districts are probably and potentially the main resources that the people have, which they must learn to use to imagine and construct a better future for themselves. The festivals provide an opportunity for the people to concentrate on resources, imagination and efforts towards improving and making their cultural expressions more refined and beautiful and helping to build self-confidence.

More outside appreciation, including from foreign tourism, would help contribute to an improved sense of confidence of the people and more economic benefits for the local communities. This, in turn, would provide the necessary stimulus for further refinement and creativity. As things stand, the powers of cultural resources in the Chittagong Hill Tracts now only exist as a potential, not even partially developed to any significant level. However, if the cultural resources of the Chittagong Hill Tracts are carefully nurtured and developed, they could help the indigenous and ethnic minority communities of the area not only survive but thrive as distinct proud peoples, together and side by side with the Bengalis of Bangladesh.