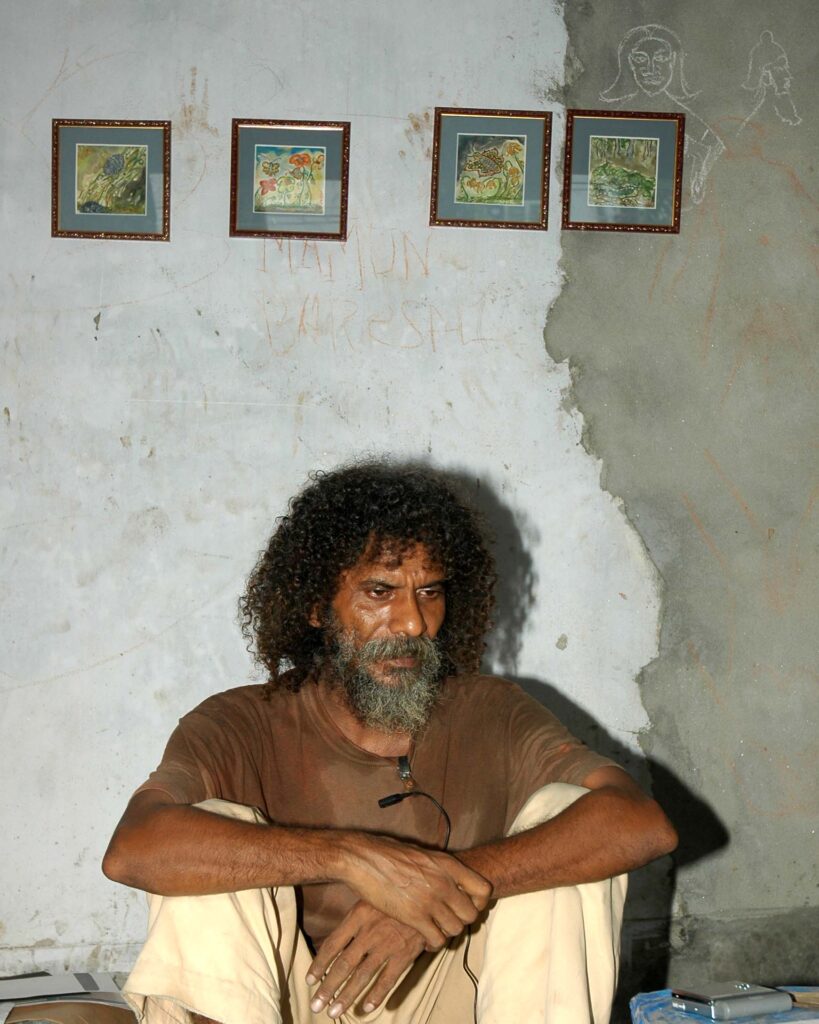

Bhaskar Rasha operates from a small studio in Kataban on the second floor of a complex of shops and studios. He specialises in producing works of sculpture based on ancient Bengali tradition, including terracotta making. He also paints and the four paintings below and above depict the life cycle of a butterfly through four distinct phases of its life.

He was born in Faridpur but has lived in Dhaka City since 1958, and has been practising art for the past 30 years. His parents, sisters and friends have always supported and encouraged him in this regard. On the question of what attracted Bhaskar to practice this art form, he says that it is the only three-dimensional art that people want to touch. People listen to music, watch dances and observe paintings, but when it comes to statues they want to touch. This is what attracted him to develop a specialism in the art of sculpture production.

Bhaskar is unlike anybody else, and also looks very unconventional. He has a fearless character and strong political and moral views. It was his dislike for dictatorship and as a protest against the military rule of General Ershad that he publicly burnt some of his important works in 1987.

What about education and how did he come to develop his skills in this area of work? According to Bhaskar, he self-taught this art form, aided by books. He feels that books are the best educational guides in life. Although he enrolled at Bulbul Academy many years ago he never completed his studies. That is the reason why he always tells people that he is still in his first year’s course.

When he won the Asian Gold Prize in 1983 (second Asian Bi-annual), he told people that he was a first-year student. Although to date his works are displayed at the Shilpakala Academy, Bangla Academy, Jagannath College, Kabir Foundation, Janata Bank, National Museum and in many other places, he still feels let down that the government of Bangladesh has not commissioned any works from him. Many people from outside Bangladesh have also commissioned his works. Had the government commissioned him to produce some works, then more people in the country could have learnt and benefited from this 1,000 years old Bangla art heritage.

On the question of why he does not lobby the government in this regard, he says that if you do that then you will have to compromise your principles because they will want a trade-off. He, however, feels that the government, seeing the value of his work should commission his works unconditionally. In that way, he will not have to change and compromise his principles, which he will never do anyway. As the government is not coming to him he feels that this is depriving him of his rights as well as preventing the country from benefiting from his talents. But as he is committed to preserving and developing this ancient Bangla art he will go on working. He is always ready to co-operate when they are unconditional. Only the value and quality of his works should determine their future.

On the question of his favourite food and clothing, he says that a long time ago he managed to cleanse himself of any desires for anything favourite. Therefore, he does not crave for anything and does not have anything which he calls favourite.

He has learnt to exercise and keep himself well, even eradicating some illnesses that he had suffered previously, such as TB, a tumour, etc. Bhaskar says that just like how he learnt the art he also self-taught exercise and daily undertakes one and half hours of rigorous physical activities. This keeps him well. Concerning the recent westernisation trends in Bangladesh, in terms of food, music and clothing, Bhaskar’s point is that due to a lack of national feeling people are becoming more and more outside oriented and losing the love for one’s culture and country. He blames bad politics for this and feels that without improving the political situation it will not be possible to improve our national feeling. Bhaskar feels that anything that erodes national feeling is a bad thing.